A ROADMAP FOR USING THE GRI FOR SOCIETAL IMPACT REPORTING

By Brett Crawford, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Department of Management

Chandresh Baid, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Department of Management.

Societal impact reporting challenges are systemic for companies across West Michigan and, for that matter, everywhere. Outside stakeholders—investors, customers, accreditors, partners, etc.—are asking for transparency when it comes to societal impact. We define societal impact as generating a significant, positive effect on social, environmental, and economic challenges and opportunities. In academic terms, stakeholder theory has brought with it an expectation that companies transparently and regularly disseminate their societal impact story. Stakeholders want to know what values a company embodies and how they are actionably pursuing those values. In practical terms, many West Michigan companies argue that they have been engaged with societal impact, at least in some capacity, for decades, but are now tasked with aggregating and communicating those efforts outwardly. But how? And is simply summarizing current doings enough?

In response to this need, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) is the most widely adopted and legitimate tool for addressing this seemingly universal challenge (Etzion & Ferraro, 2010; Levy, Szeinwald & De Jong, 2010). The GRI has been described as “the preeminent global framework for voluntary corporate environmental and social reporting” (Levy et al., 2010; also see Gehman, 2011). Indeed, more companies use the GRI to support their societal impact reporting efforts than any other tool out there. From a practice perspective, the GRI offers a readymade set of metrics and categories built off the triple bottom line (people, planet, and profit), including universal-, sector-, and topic-based standards. From a process perspective, the GRI presents companies with a roadmap and guidance on how to best engage with stakeholders, including the integration of those engagements into strategy and reporting. It helps companies clearly detail their impact through what Wickert (2021) dubs a “society-centric” focus, that is, positive effects a business has on broader social, environmental, and economic challenges.

Getting Started with the GRI

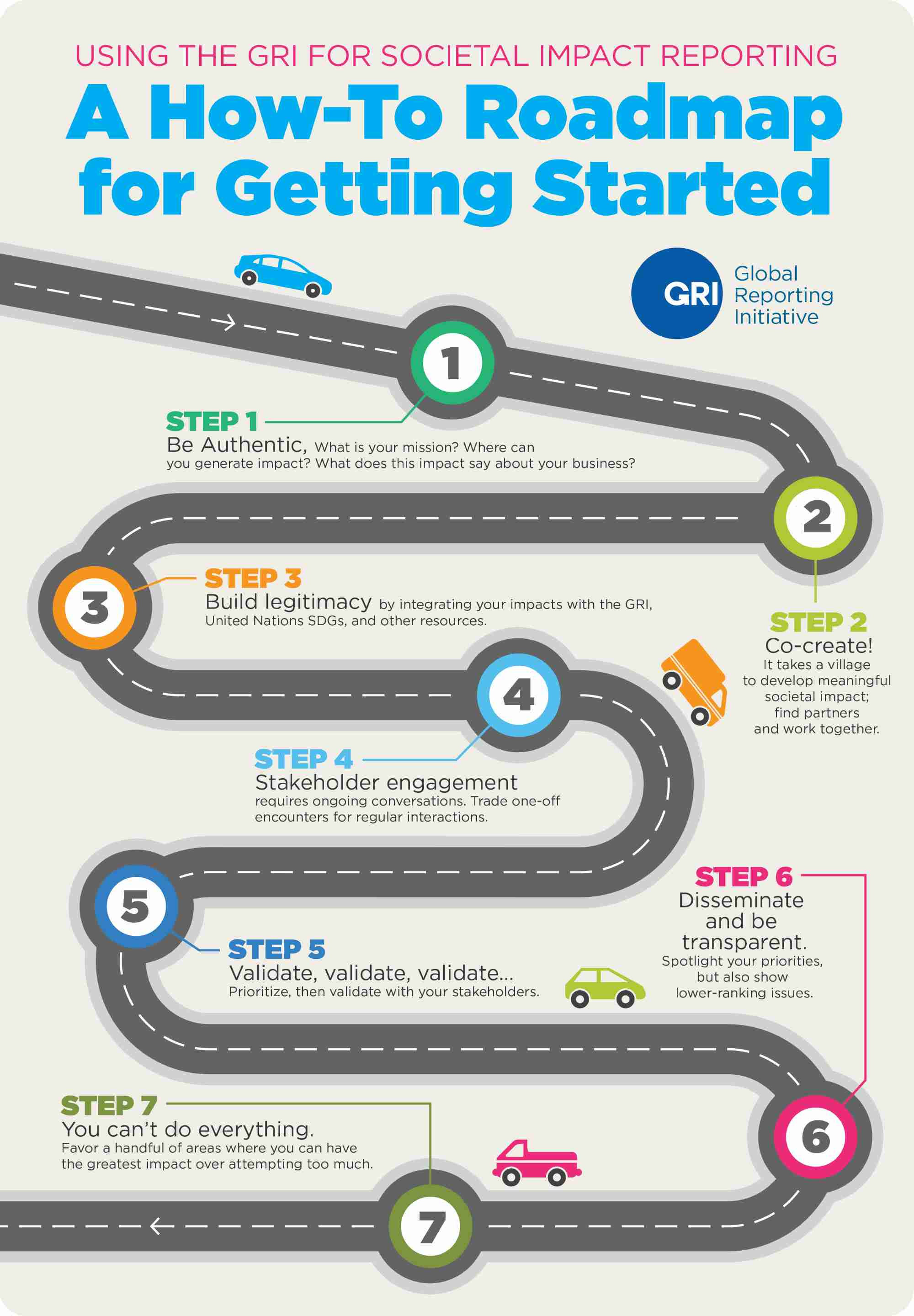

Using the GRI requires much more than simply counting what an organization is already doing, force-fitting those current doings with the GRI metrics (i.e., square pegs into round holes), and communicating an incomplete story through a societal impact report (see Figure 1). One key aspect of reporting with the GRI tool is materiality, which becomes actionable through what is known as a materiality analysis. A materiality analysis aims to detect interests and issues shared by both the company conducting the analysis and its stakeholders (Torelli, Balluchi & Furlotti, 2019). Through interaction and the ranking of interests and issues, a company develops an understanding of priorities, both for themselves and for their stakeholders. Thus, this process encourages organizations to move beyond static stakeholder mapping to engage with their stakeholders and co-create goals and metrics together. Materiality analyses help develop an organization’s future trajectory, and the processes used become crystalized in the reports themselves. Moreover, organizations using the GRI are expected to offer transparency through descriptive step-by-step accounts of their materiality analysis in their reports.

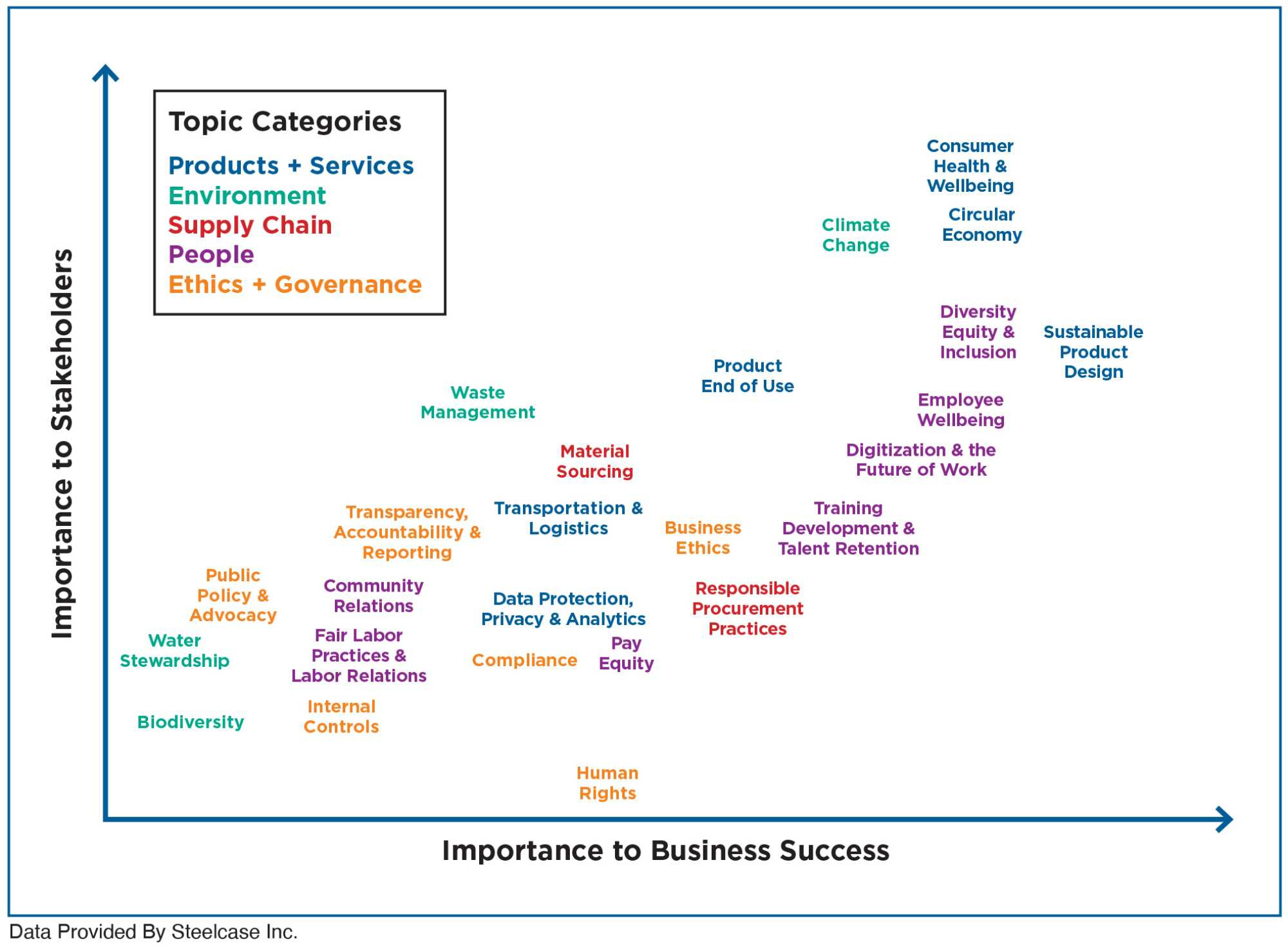

For example, Steelcase completed their most recent materiality analysis in 2020 through a four phase process (Steelcase, 2021, p. 14). During the first phase, Steelcase identified key stakeholder groups and a robust list of material topics of potential interest. During the second phase, Steelcase sought prioritization of those material topics through surveys, interviews, and workshops, leading to a matrix detailing a ranking of importance. In the third phase, Steelcase’s senior leadership validated the outcomes of phase two, assuring alignment between priorities and the overall strategic trajectory of the company. Finally, the fourth phase is performed through annual reviews, including possible adjustments to priorities, before the next full materiality analysis is conducted. Illustrated in Figure 2, Steelcase’s topic categories transcend the social, environmental, and economic categories that comprise the GRI.

Of note, not only does the GRI offer metrics and categories to support societal impact reporting, along with a roadmap and processual guidance on stakeholder engagement, but companies commonly use the GRI categories and standards as the index of their reports. In a sense, the GRI functions as a skeleton for impact reporting, where companies can animate the standards through narratives and data, but the index and, therefore, flow of the reports has inherent similarities. The GRI standards are the bones of the reports. Using the GRI as the report’s index also improves comparability across companies, even while the structure of reporting maintains flexibility in self reporting. In other words, the available standards are the same, but companies pick and choose which standards to report disclosures on.

Putting the GRI to Use

When it comes to using the GRI, we observe a number of important trends, mostly in relation to materiality analyses as the foundation for engaging stakeholders. First, interactions amongst stakeholders have become much more than feedback loops, as they were with many early reports around 2010. Today, regular, scaffolded interactions are commonplace to establish and pursue goals and initiatives, as well as measure and disseminate impacts (Crane & Glozer, 2016). Second, early materiality analyses helped the organization conducting them to define their own future social, environmental, and economic pursuits. More recently, we see all stakeholders involved adopting such initiatives. Thus, the metrics illustrating performance outcomes have become shared resources; all stakeholders involved can use the findings in their own reports. This has helped propagate non-financial reporting further, as more and more companies have clear and shared initiatives and performance indicators to report on. Third, we imagine that the GRI is primed to expand beyond its original audience of companies to also serve as an invaluable tool for noncorporate entities. For instance, the Seidman College of Business is currently going through its normal reaccreditation cycle, this time, with the addition of a societal impact standard as the AACSB is following a similar path as other accreditors in evaluating member organizations’ performance with regards to social, environmental, and economic parameters. To be sure, the GRI can function as a viable tool for coopting best practices from the corporate world and applying them to educational settings. Perhaps through that process, usage of the GRI can also translate to teaching the GRI to tomorrow’s sustainability professionals through action-oriented experiential learning with very practical applications. Such education initiatives could produce graduates with competencies that enhances future employers’ use of the GRI. We see this is especially significant for small and medium sized companies who might be facing increased pressures to disseminate societal impact reports, but also have to account for a different set of resource constraints. Moreover, adoption of the GRI by noncorporate entities would enhance reporting over time, as well as comparability across nonprofit, government, and educational sectors.

It is also valuable to consider what the implications are of not using the GRI or if other approaches are viable. We offer a pair of responses. First, because the GRI usage by large companies has become institutionalized (Etzion & Ferraro, 2010; Levy et al., 2010) choosing not to use the tool is potentially risky, especially when stakeholders expect certain levels of engagement and transparency. Additionally, assuming the reporting is honest, accurate, and comprehensive, all of which the GRI defines as critical characteristics of good reporting, there is much to be gained. Strengths will be spotlighted. Areas of underperformance will become obvious. Together, both observations can lead to actionable responses, doubling down on areas of excellence and filling gaps relative to an organization’s weaknesses when it comes to societal impact.

But what about smaller companies? For small businesses, the span of focus becomes much more localized. Thus, we imagine that if many small businesses within West Michigan conducted their own materiality analyses, they would likely come to very similar conclusions because of shared and overlapping stakeholders. Thus, instead of placing the burden of responsibility on small businesses to conduct these analyses, perhaps organizations supporting the region’s small businesses become the entities that perform regional materiality analyses. Small businesses can then compare and contrast priorities of regional stakeholders with their own priorities. Regional materiality matrices would become a shared resource, aiding small businesses in their pursuits of impact reporting, while also alleviating some of the major resource burdens. We might also see more and more small businesses integrating their strategies with regional identity markers, such as the preservation of the Grand River, the Great Lakes, and native flora and fauna. These values already come through strongly with small businesses such as Forever Great (Forever Great, 2021) and Lake Effect Phone Repair (Lake Effect Phone Repair, 2021), both formed by GVSU alumni. Perhaps the regional entity performing a regional materiality analysis would help smaller companies engage with the GRI and also serve as a catalyst for expanded societal impact reporting.

Second, alternatives to using the GRI do exist, including impact reports produced by Certified Benefit Corporations (B Corps). The Gluten Free Bar, for example, produces annual impact reports as part of their B Corp status. Although most B Corps do not use the GRI, the reporting processes developed through this collection of companies have become incredibly effective at disseminating social, environmental, and economic impacts. Moreover, unlike societal impact reports by large companies using the GRI, which are voluntary self-disclosures, B Corps are required to produce impact reports to maintain their B Corp status. These reports are oftentimes much more concise than reports by larger companies using the GRI. Case in point, The Gluten Free Bar’s 2020 Sustainability Report is nine pages long from cover to cover and includes multi-year performance impacts (Gluten Free Bar, 2020). They also archive all of their annual impact reports online, so that stakeholders can engage with their historical reports. For comparison, Steelcase’s 2021 Impact Report is 77 pages in length, Herman Miller’s 2021 Better World Report is 44 pages long, and other companies’ reports are frequently much longer. However, one could argue that more concise reports improve accessibility, clarity, and perhaps engagement by more stakeholders.

Making a positive impact is the goal, whether an organization is for-profit or not for-profit, small or large, old or new, or has been focused on societal impact for decades or is just getting its feet wet. Tools, such as the GRI, exist to aid the reporting process by providing a roadmap and offering guidance to help position organizations to proactively engage with social and environmental challenges (Ferraro, Etzion & Gehman, 2015), which their stakeholders have come to expect.

References

Crane, A., & Glozer, S. (2016). Researching corporate social responsibility communication: Themes, opportunities and challenges. Journal of Management Studies, 53(7), 1223-1252.

Etzion, D., & Ferraro, F. (2010). The role of analogy in the institutionalization of sustainability reporting. Organization Science, 21(5), 1092-1107.

Ferraro, F., Etzion, D., & Gehman, J. (2015). Tackling grand challenges pragmatically: Robust action revisited. Organization Studies, 36(3), 363-390.

Forever Great. (2021, December 3). Our Story – Forever Great. https://forevergreat.co/pages/our-story

Gehman, J. (2011). The global reporting initiative: 1997-2009. Available at SSRN 1924439.

Gluten Free Bar (2020). Sustainability Report. https://theglutenfreebar.com/pages/sustainability

Lake Effect Phone Repair. (2021 December 3). Lake Effect Phone Repair – E-Recycling Program. https://www.lakeeffectphonerepair.com/electronics-recycling

Levy, D. L., Szejnwald Brown, H., & De Jong, M. (2010). The contested politics of corporate governance: The case of the global reporting initiative. Business & Society, 49(1), 88-115.

Steelcase. (2021). Steelcase Impact Report and GRI. https://www.steelcase.com/content/uploads/2021/09/Steelcase-Impact-Report-and-GRI-2021.pdf

Torelli, R., Balluchi, F., & Furlotti, K. (2020). The materiality assessment and stakeholder engagement: A content analysis of sustainability reports. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(2), 470-484.

Wickert, C. (2021). Corporate social responsibility research in the Journal of Management Studies: A shift from a business‐centric to a society-centric focus. Journal of Management Studies, online first.