Health Care Overview

By Cody Kirby, Ph.D., Visiting Faculty, Department of Economics, Seidman College of Business, Grand Valley State University

This section examines key healthcare trends in the KOMA (Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan) and Detroit (Macomb, Oakland, Wayne) regions, including healthcare access, health status, mental health, general health risk factors (such as alcohol consumption, smoking, and obesity), vaccination behavior, and major chronic conditions. Building on last year’s report, our primary emphasis is understanding health disparities within KOMA and the Detroit region. To achieve this, we scrutinize healthcare trends by focusing on the persistence of racial and gender gaps within and between each locality, using data from the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (MiBRFSS).

It is important to note several limitations associated with MiBRFSS data. Firstly, the estimates are derived from self-reported surveys. Consequently, the actual incidence and prevalence rates for the factors we examine using this data may vary from those reported by respondents. Secondly, a data suppression rule restricts the release of specific estimates. Certain estimates are withheld if the denominator of a weighted percentage contains fewer than 50 observations and/or has a relative standard error exceeding 30 percent. This limitation becomes particularly relevant when segmenting the data by specific demographics, notably race, sexual orientation, and gender identity. To mitigate this issue regarding race, we have combined black non-Hispanic, other and multiracial, and Hispanic categories into a “non-white” category for our analysis by race, allowing us to compare white and non-white respondents. However, even under this classification, missing estimates sometimes occur following the suppression rule. Furthermore, due to the data suppression rule, we were unable to explore most of the outcomes by sexual orientation and gender identity.

Health Insurance and Access to Care

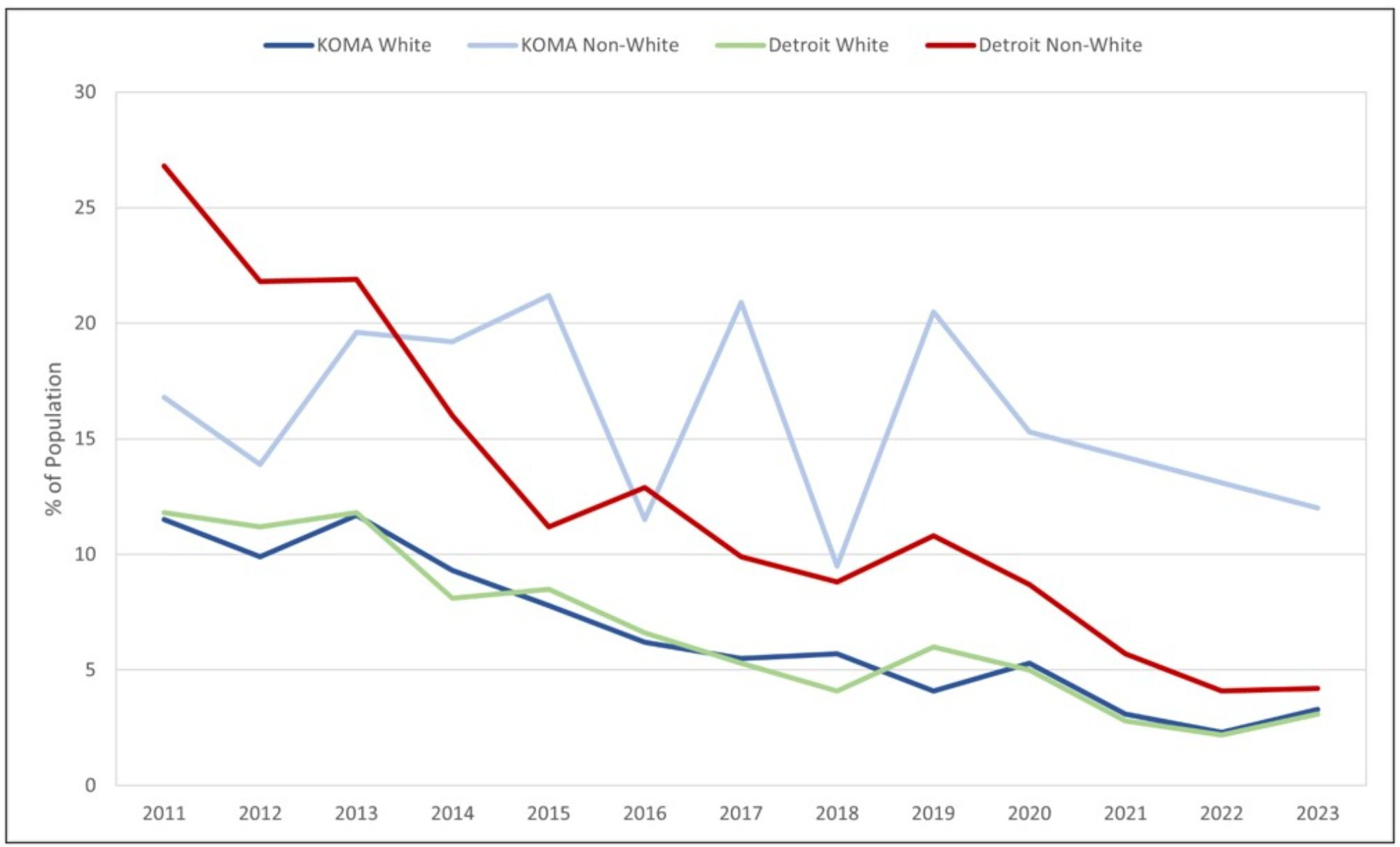

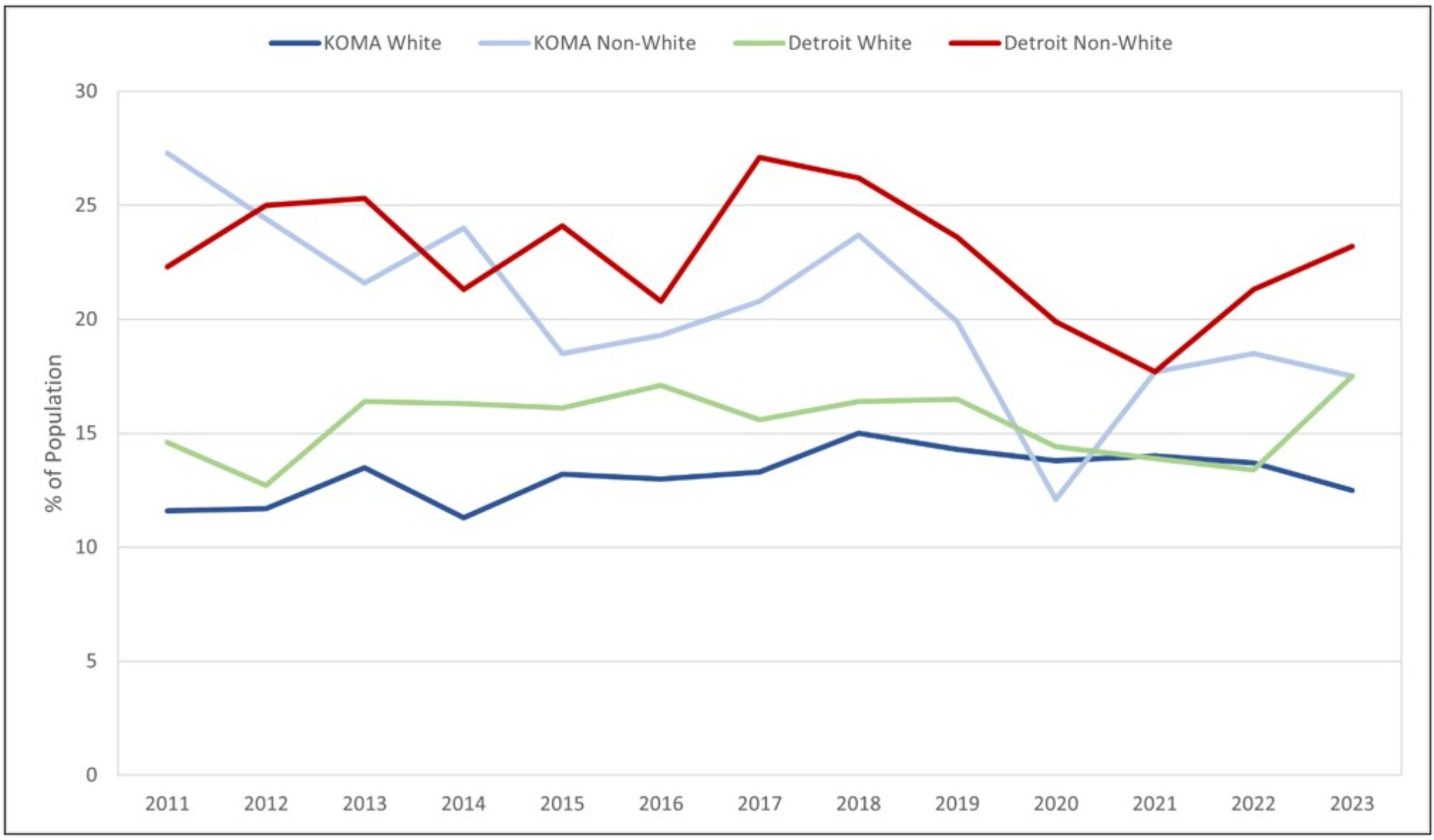

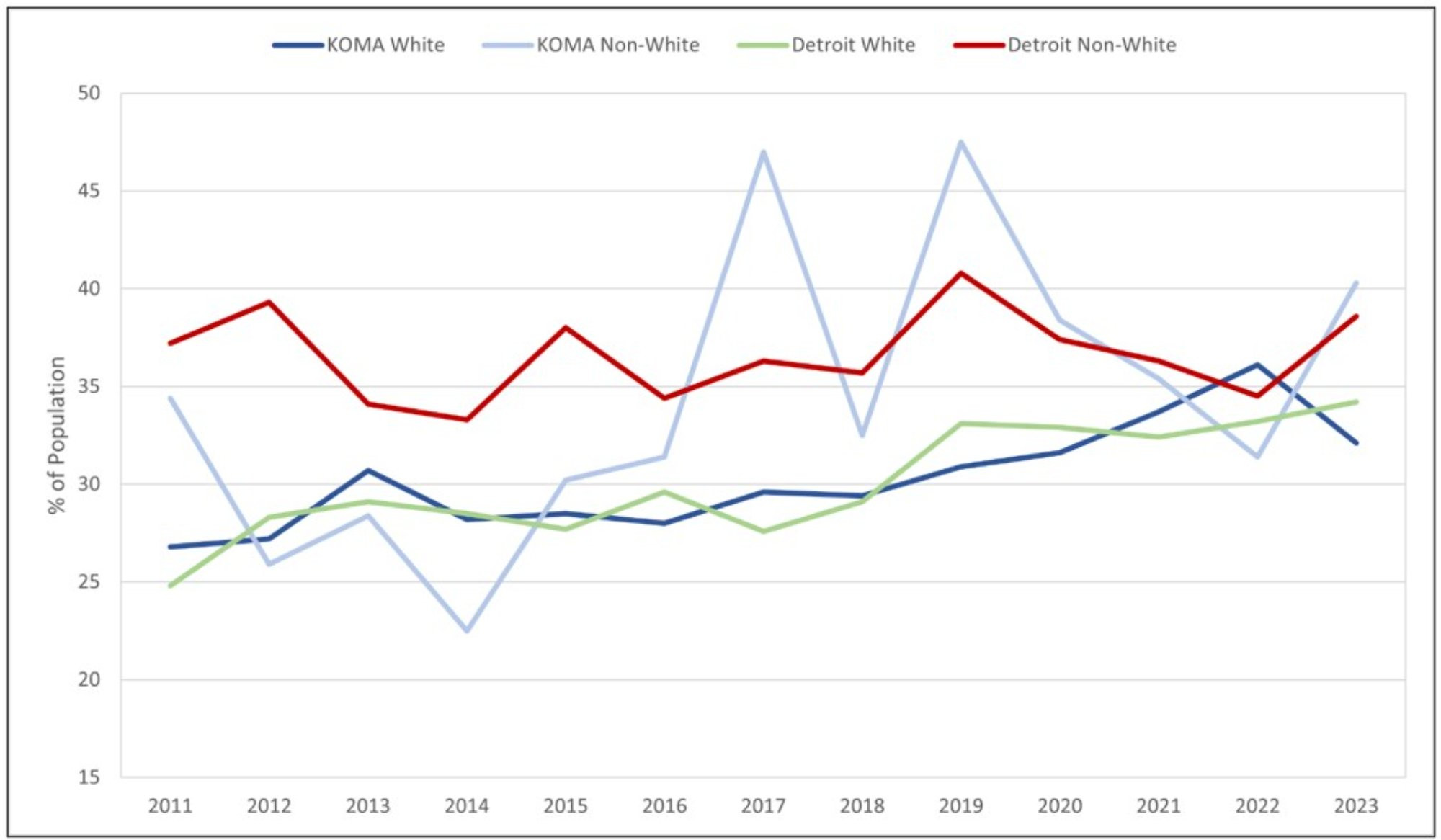

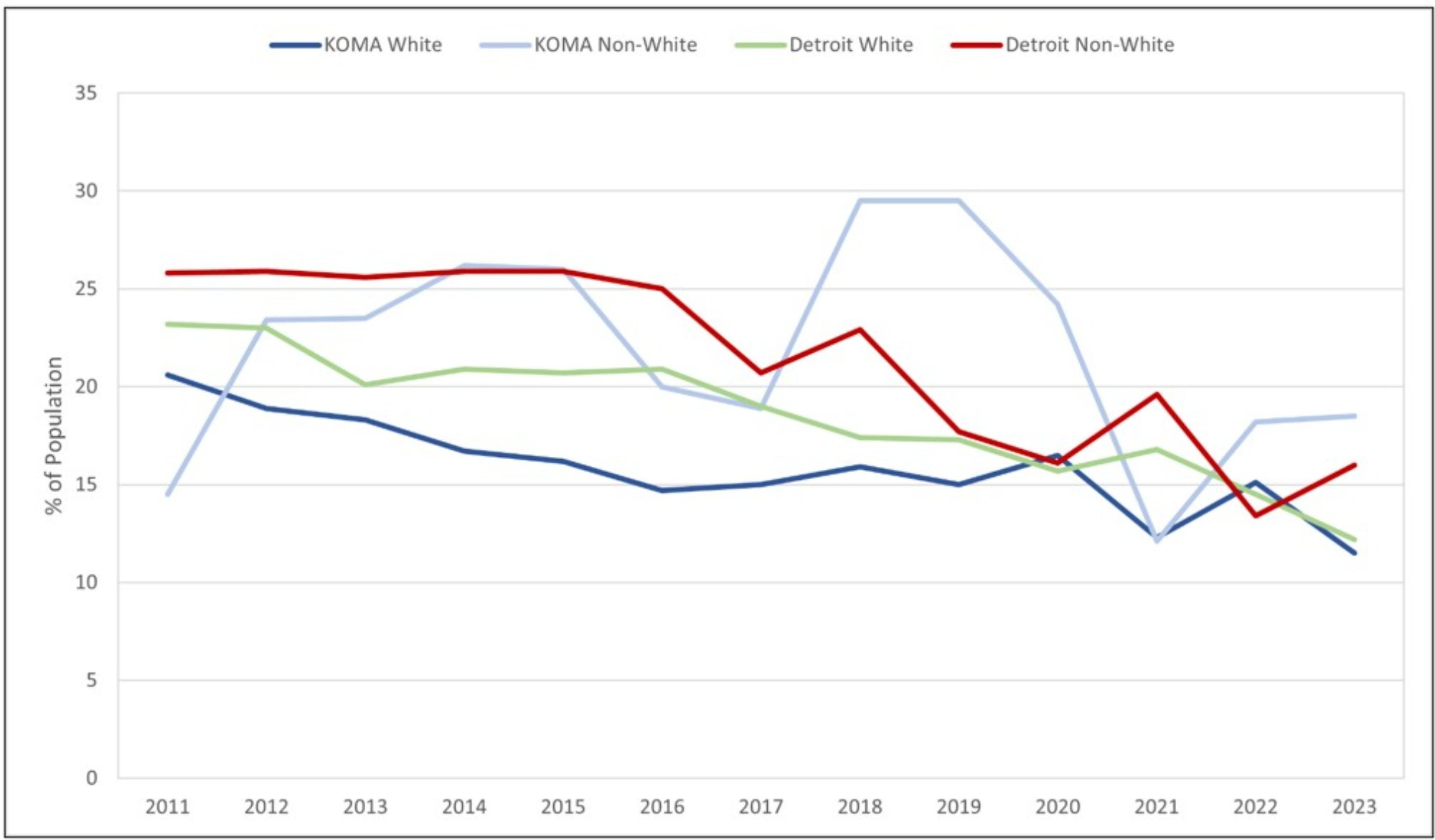

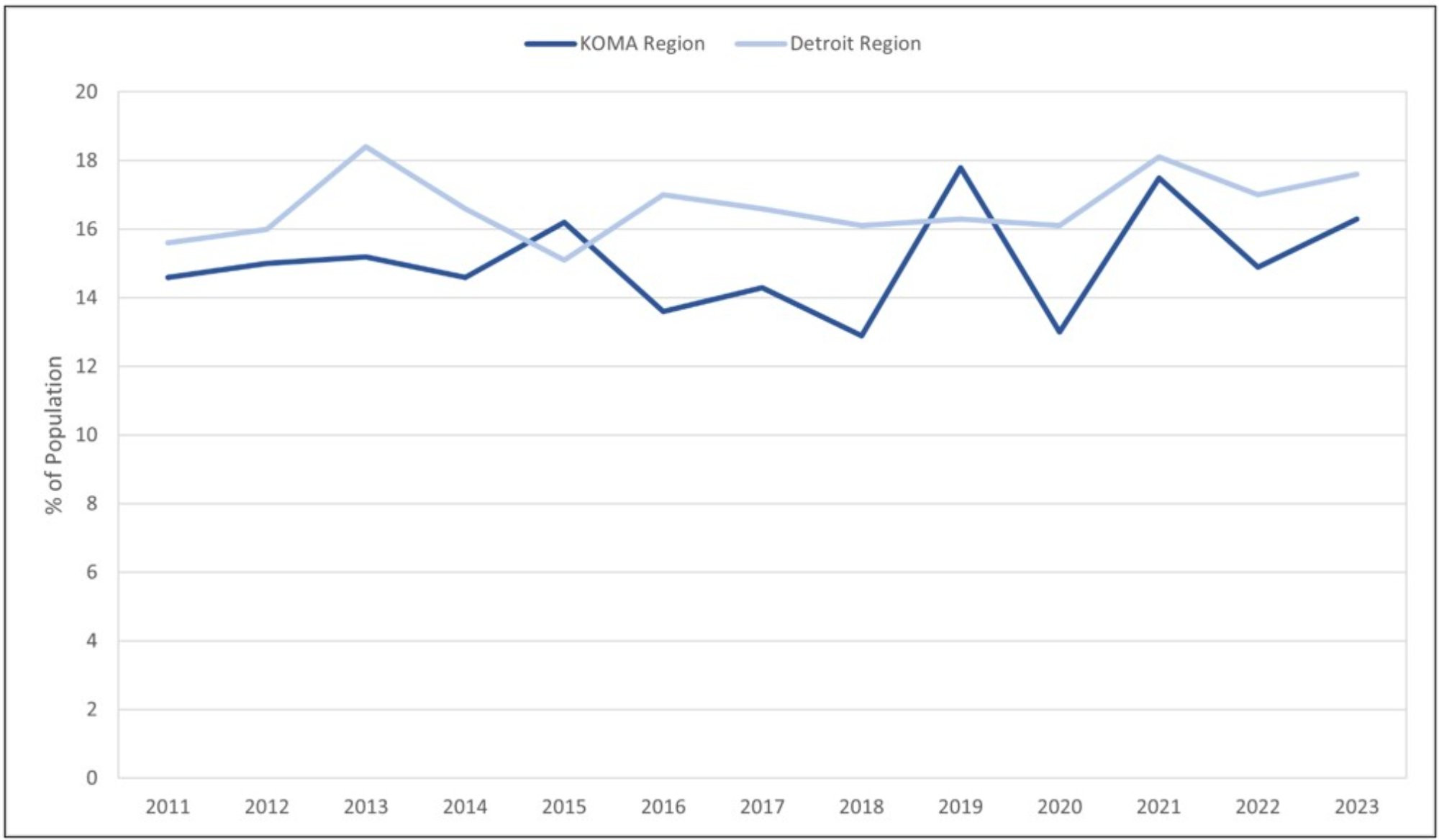

We begin our analysis by examining trends in measures related to health insurance and healthcare access. Figures 1 and 2 depict the percentage of the population in the KOMA and Detroit regions reporting no health insurance, categorized by race and gender, respectively. The uninsured rates in both regions have decreased since 2011, owing to the improving economy and the increased availability of various health insurance options under the Affordable Care Act. For instance, as of October 2024, more than 700,000 people have enrolled in the Healthy Michigan expansion of the state’s Medicaid program (MDHHS, 2024). In 2011, nearly 11 percent of the white population in both KOMA and the Detroit regions were uninsured. By 2023, this figure has dropped to approximately 3 percent in both localities. However, a distinct trend emerges when focusing on the non-white population.

Figure 1: No Health Insurance by Race, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 1 displays the prevalence of those reporting no health insurance by race and region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. Insurance access has increased by 58.3% and 32.0% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. Similar trends hold across all data strata.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

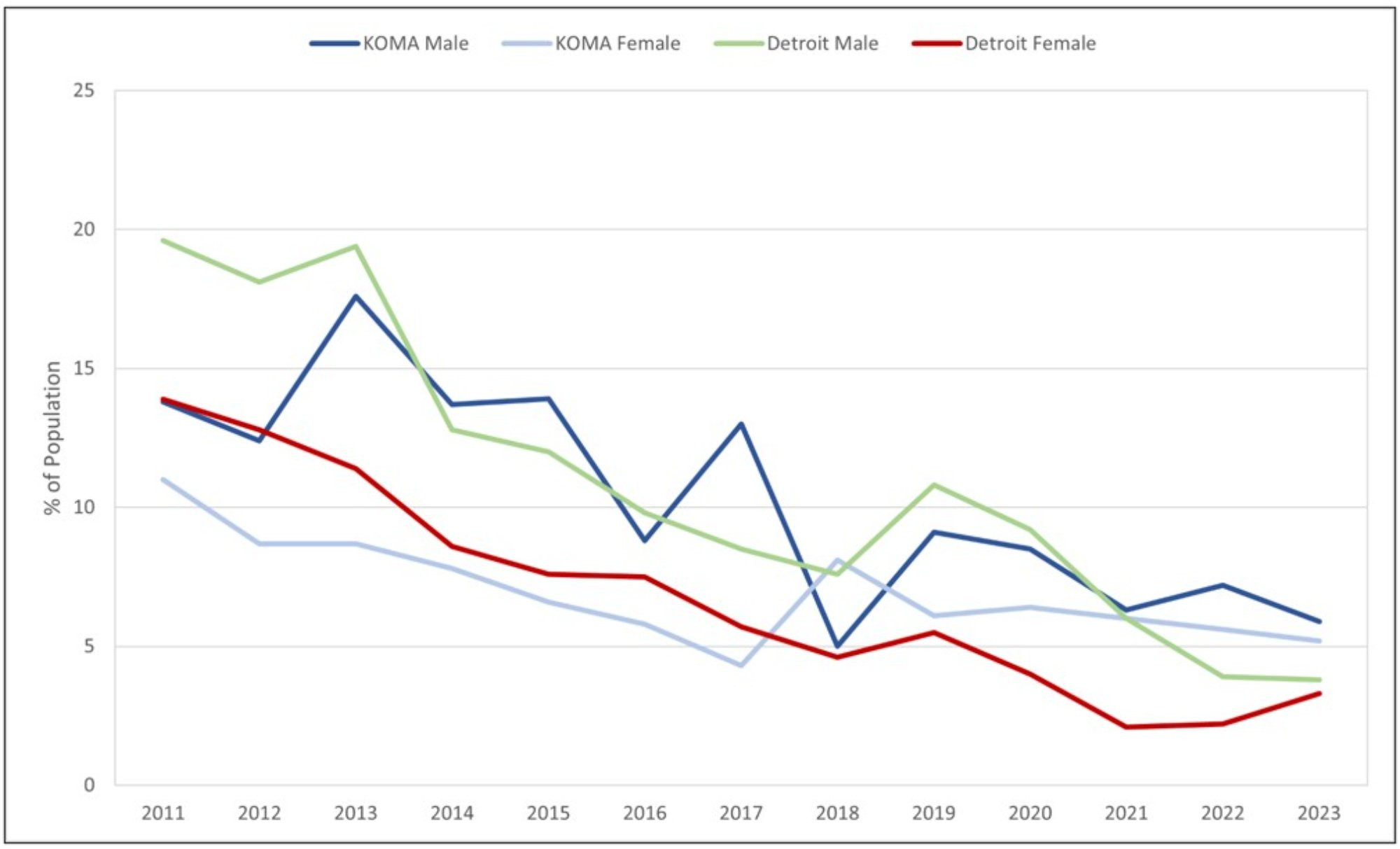

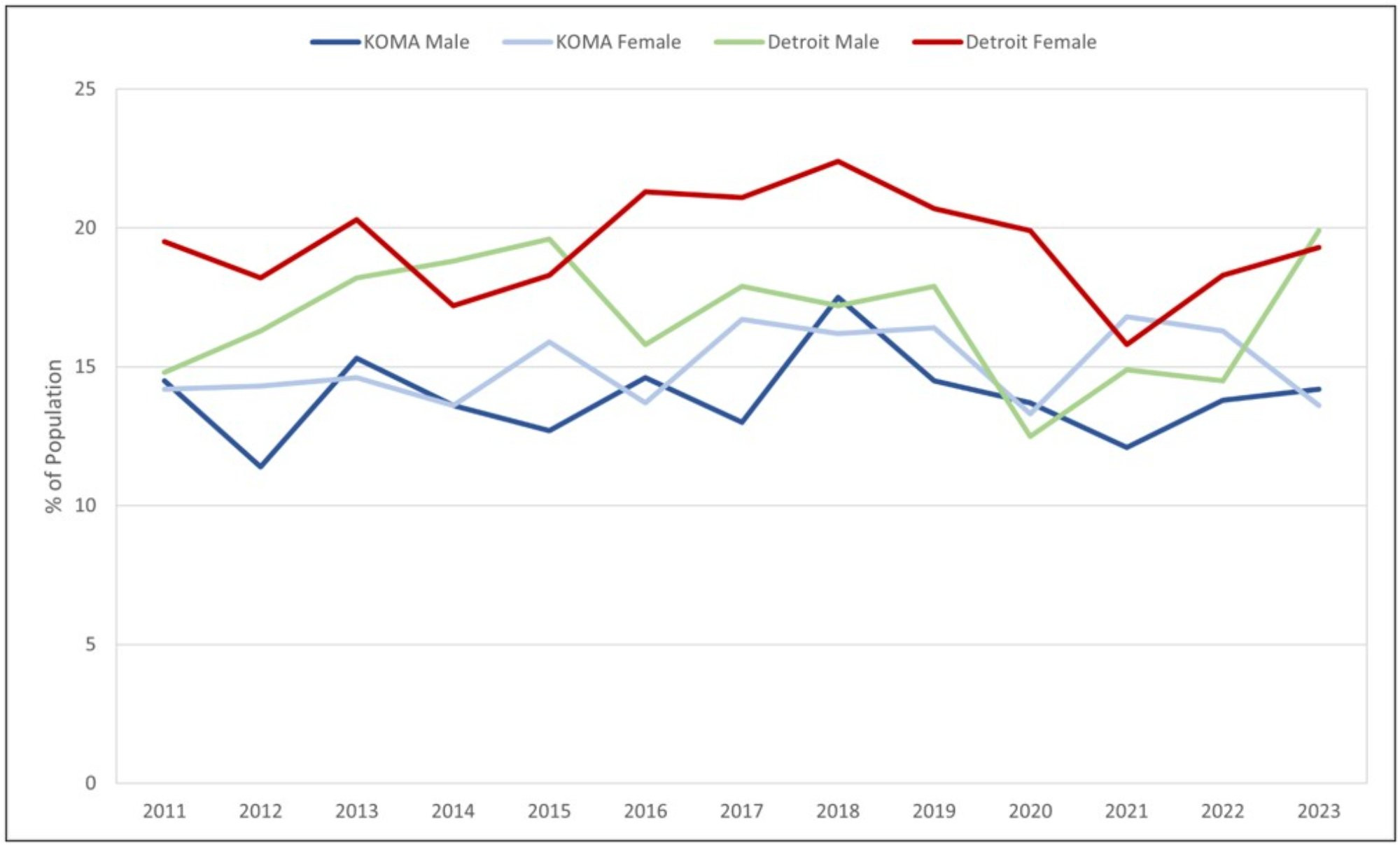

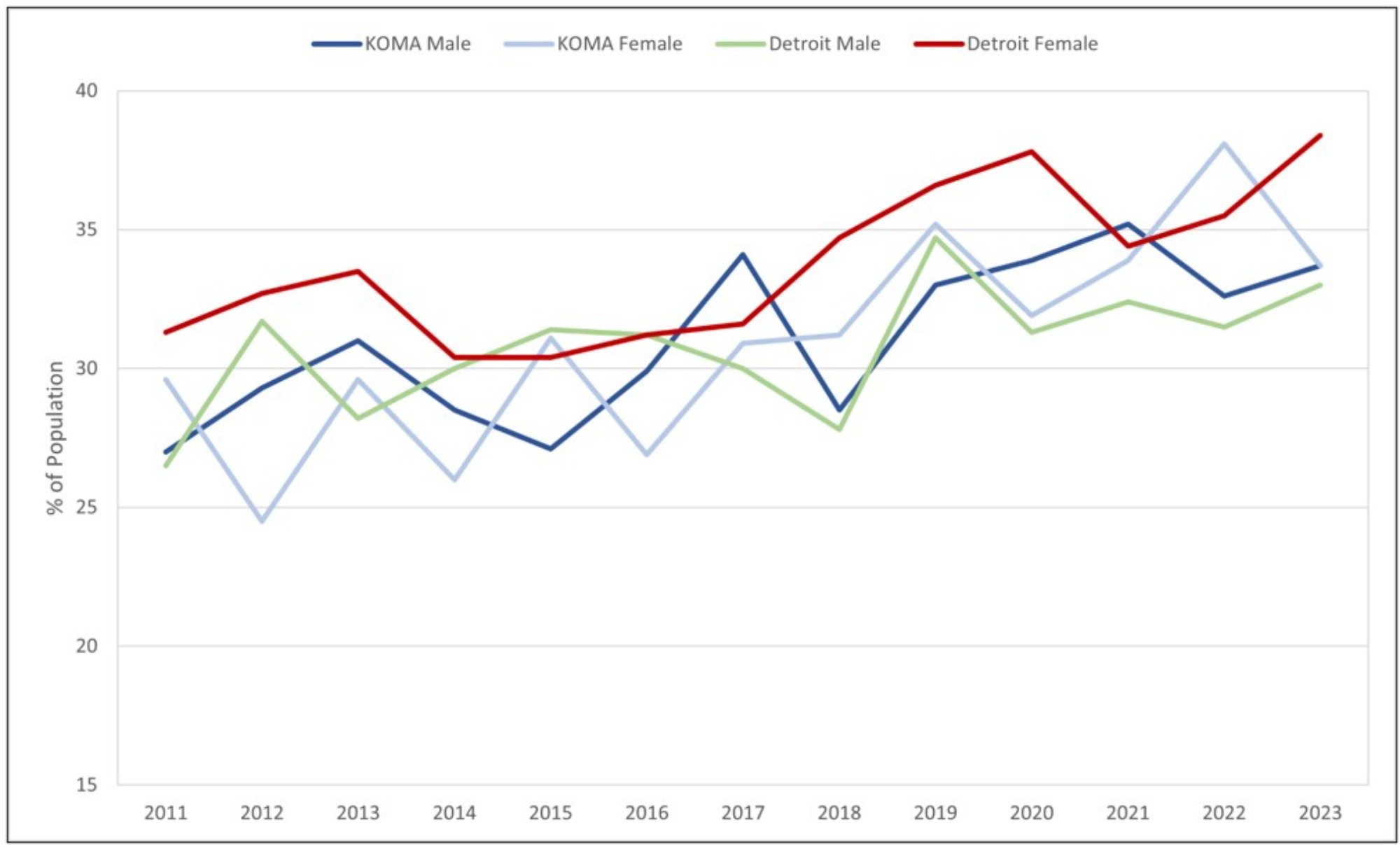

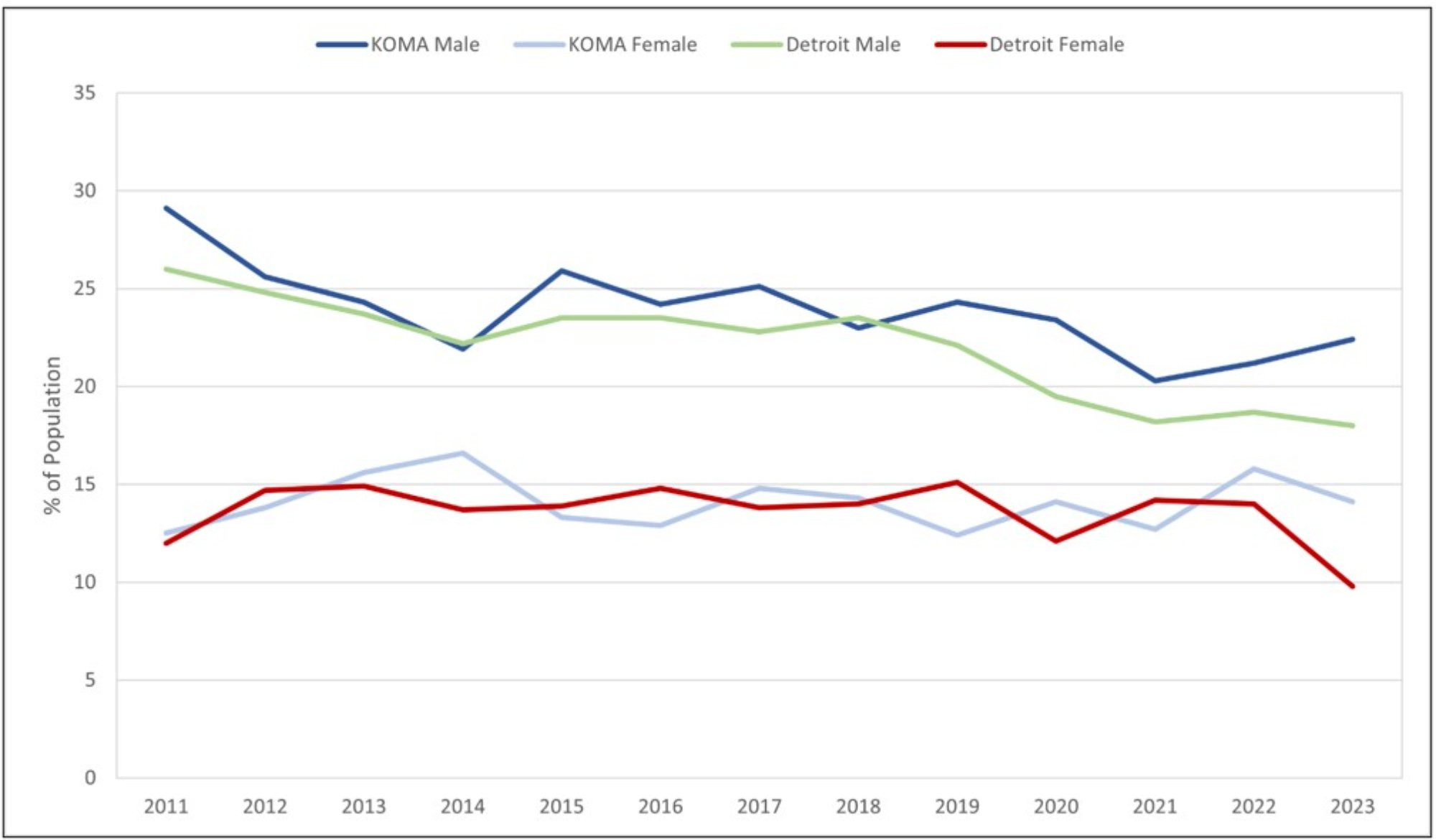

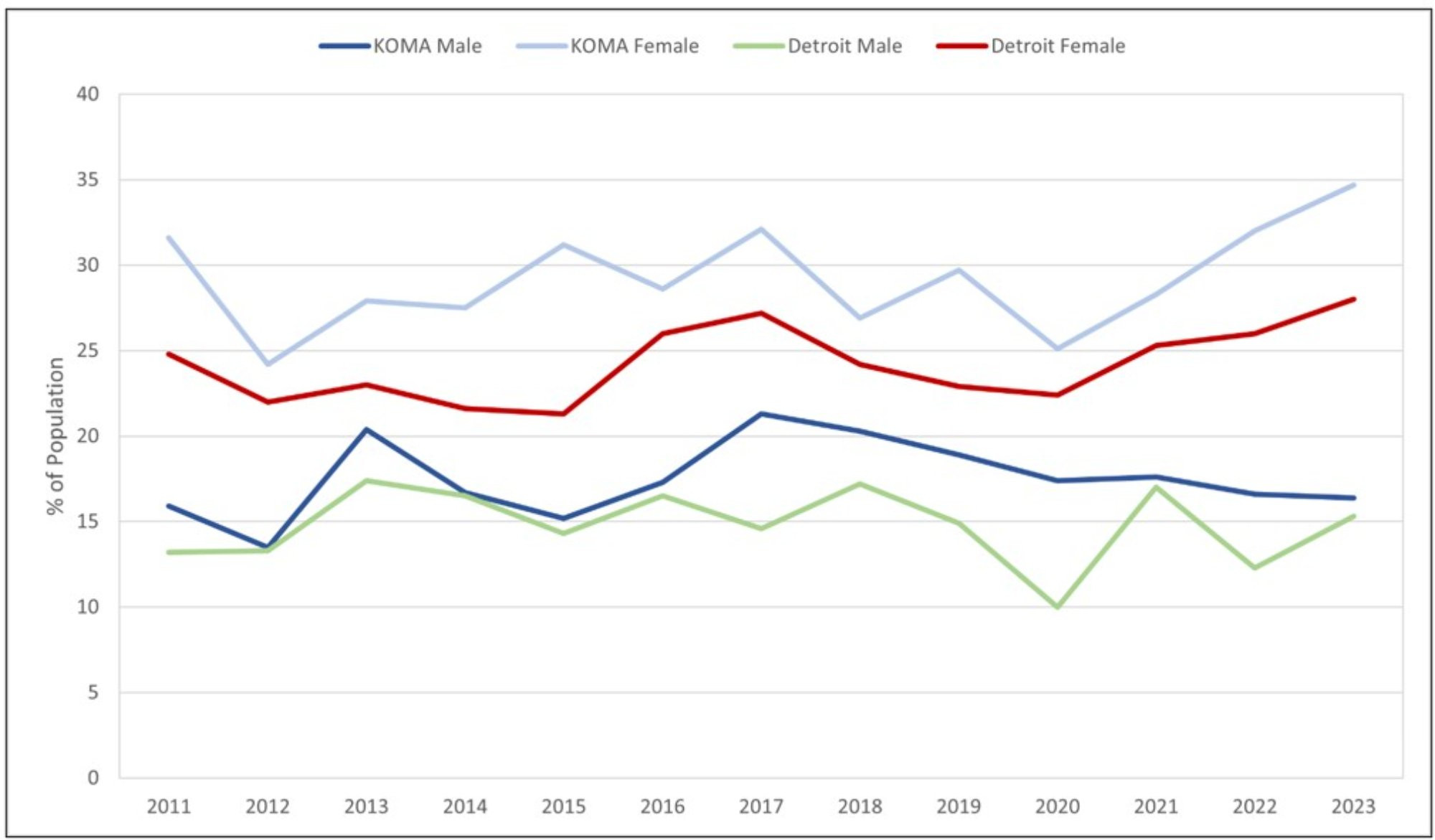

Figure 2: No Health Insurance by Gender, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 2 displays the prevalence of those reporting no health insurance by race and region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. Insurance access has increased by 58.3% and 32.0% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. Similar trends hold across all data strata.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

It is noteworthy that while the trend of having no health insurance has consistently decreased among Detroit’s non-white citizens; it has displayed more variability among KOMA’s non-white residents. In other words, we do not observe a consistent gain in health insurance access among non-white KOMA residents. Specifically, non-white populations experienced a significant increase in people without health insurance in 2017 and 2019. In 2011, about 17 percent of non-white persons were uninsured in KOMA. In contrast, an average of about 21 percent reported having no health insurance in both 2017 and 2019, representing a four-percentage point increase from the level reported in 2011. This increase in the uninsured rate remains the largest compared to all other racial groups in East and West Michigan.

Consistent with Khorrami & Sommers (2021), the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in higher health insurance enrollment for KOMA residents, especially among non-white persons. In 2020, KOMA’s non-white residents observed a decrease in the uninsured population from the prior year (21 percent to 15 percent). Due to the data suppression rule, estimates are unavailable for KOMA’s non-white residents beyond 2020. As a result, we derive simple projections using a weighted average of past directional changes. Even if we disproportionately weigh the negative changes, to reflect the typically movements observed in the non-white series, a clear racial difference in KOMA emerges post-2020. By 2023, we find an average racial gap between KOMA non-white and white persons to exceed 8 percent.

When we analyze health insurance trends by gender in KOMA, we observe an overall decline in the percentage of men and women reporting no health insurance in East and West Michigan. Although there was a slight uptick in the number of males uninsured in 2019, we find a declining trend in 2020, consistent with the increased health insurance take-up observed during the pandemic.

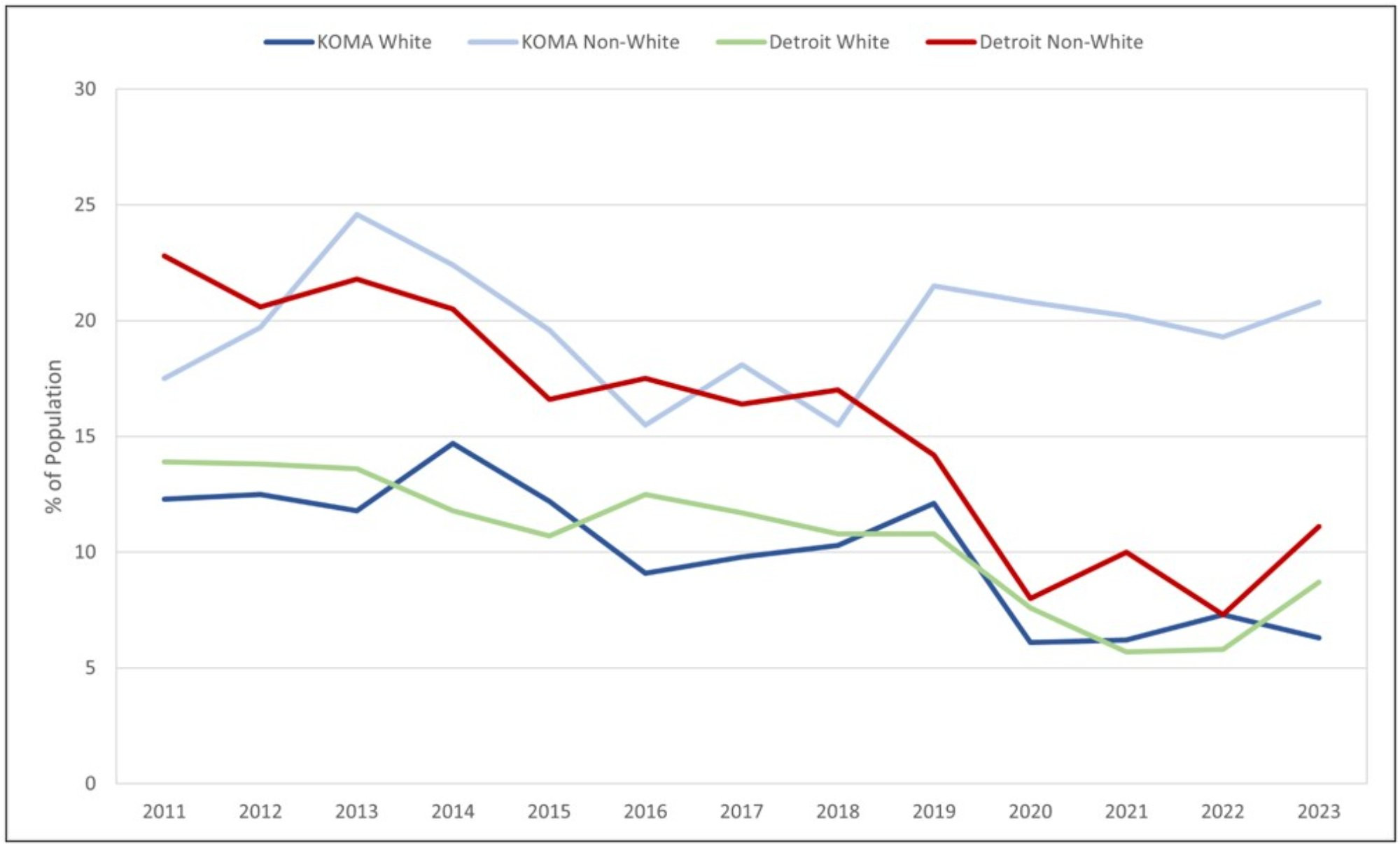

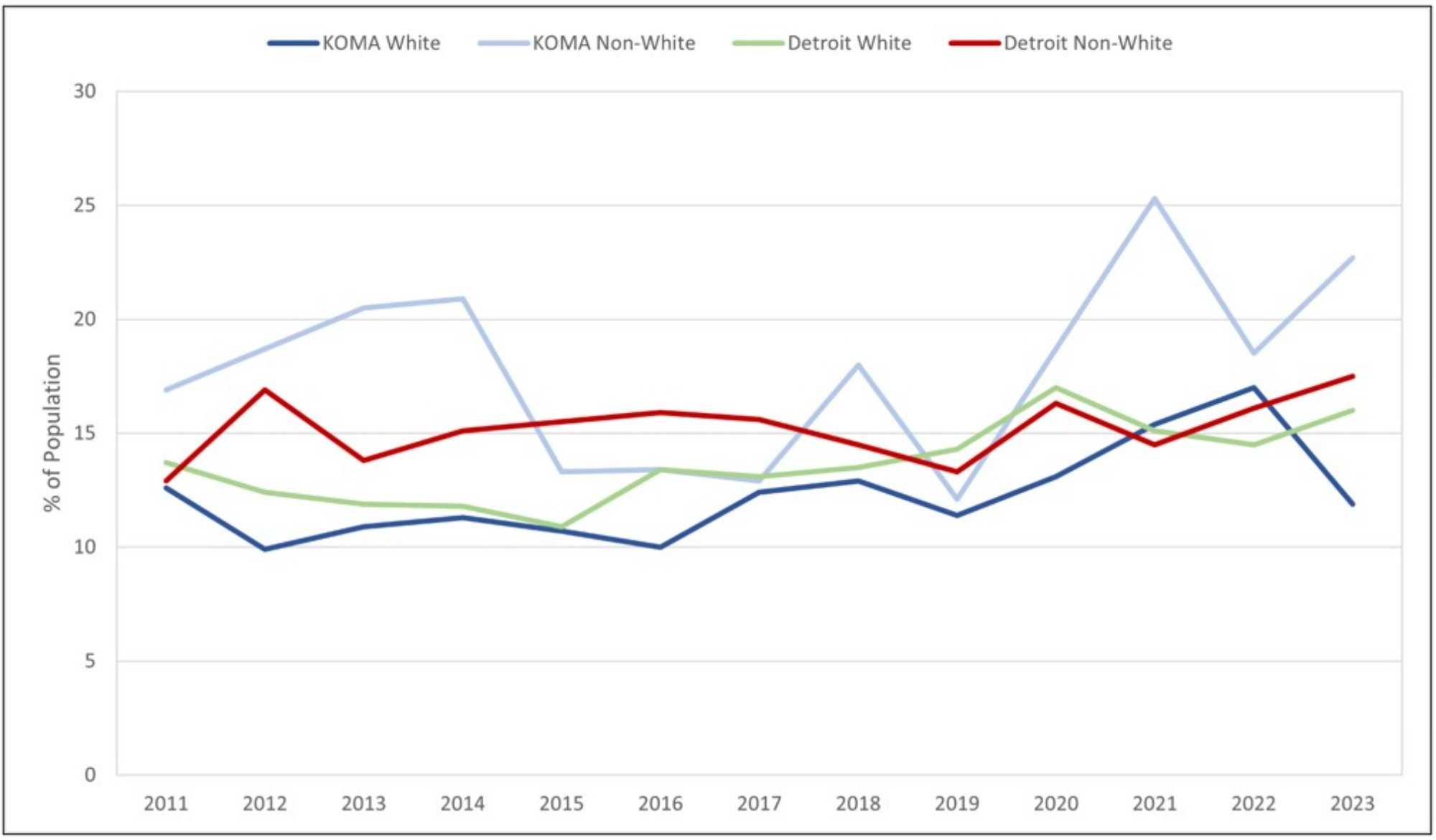

The following six figures represent various measures of healthcare access that we would expect to be impacted by the changes in insurance coverage observed in Figures 1 and 2. Figure 3 presents the reported proportions of white and non-white residents who did not receive care during the past 12 months due to cost. We observe significant disparities in affordable healthcare access between non-white and white persons, particularly in West Michigan. In 2019, 22 percent of KOMA non-white residents reported a lack of care due to cost. Since 2019, a clear divergence has occurred in affordable care between KOMA white and non-white citizens. Among KOMA’s white residents, 12 percent lacked affordable care in 2019, compared to 6 percent in 2023. By contrast, 21 percent of KOMA’s non-white citizens still report a lack of care due to cost. The racial divergence in West Michigan’s affordability is not observed in East Michigan. Between 2019 and 2023, the racial gap in the lack of care due to cost decreased by one percent in Detroit; in KOMA, that gap widened by 5 percent during the same period.

Figure 3: No Health Care Access Due to Cost by Race, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 3 displays the prevalence of those reporting no healthcare access by race and region for cost-related reasons. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that no care due to costs has decreased by 28.2% in KOMA since 2011 but has increased by 25.3% since the COVID-19 pandemic. However, for non-white residents, more report lacking care for cost reasons since 2011.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

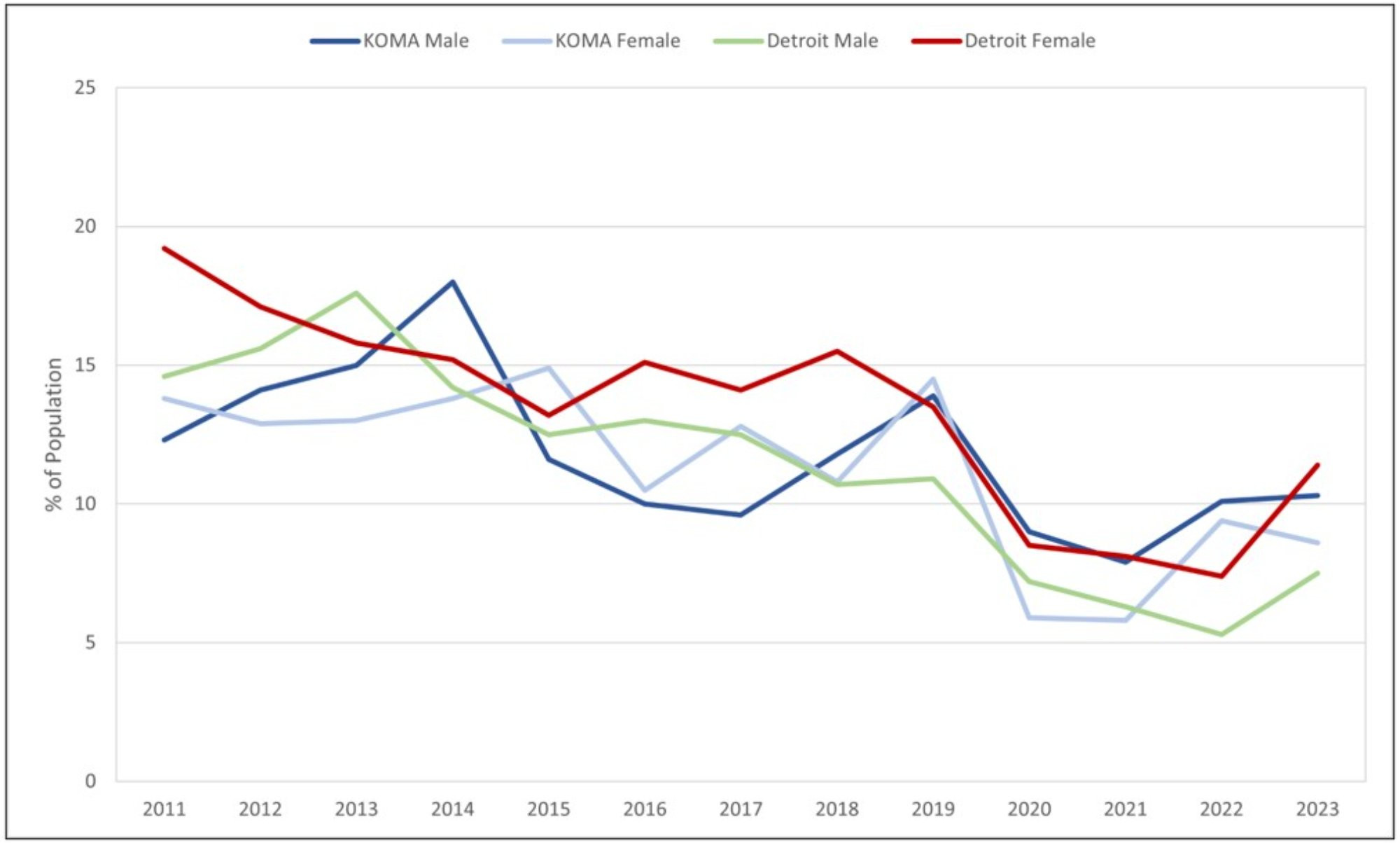

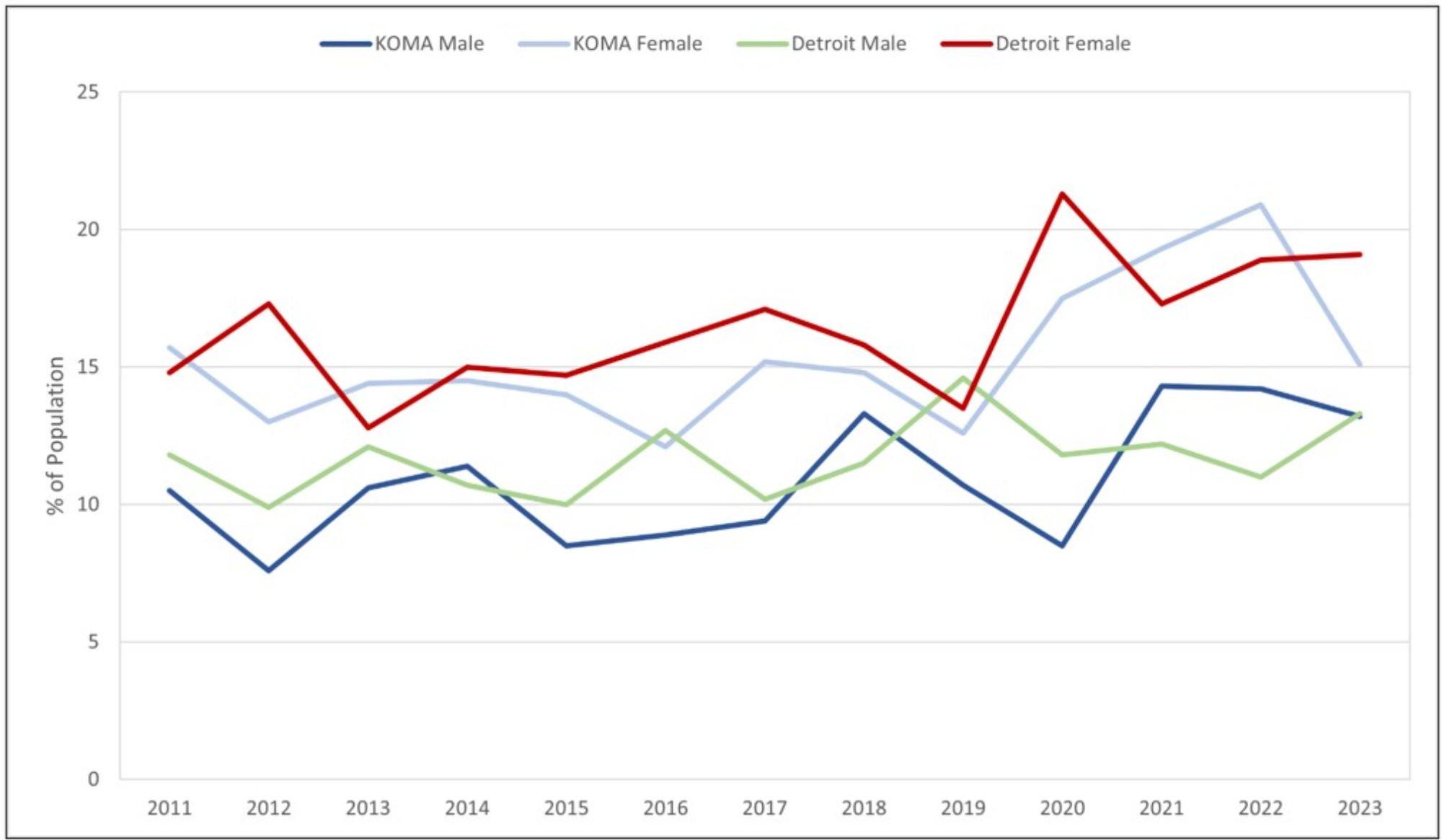

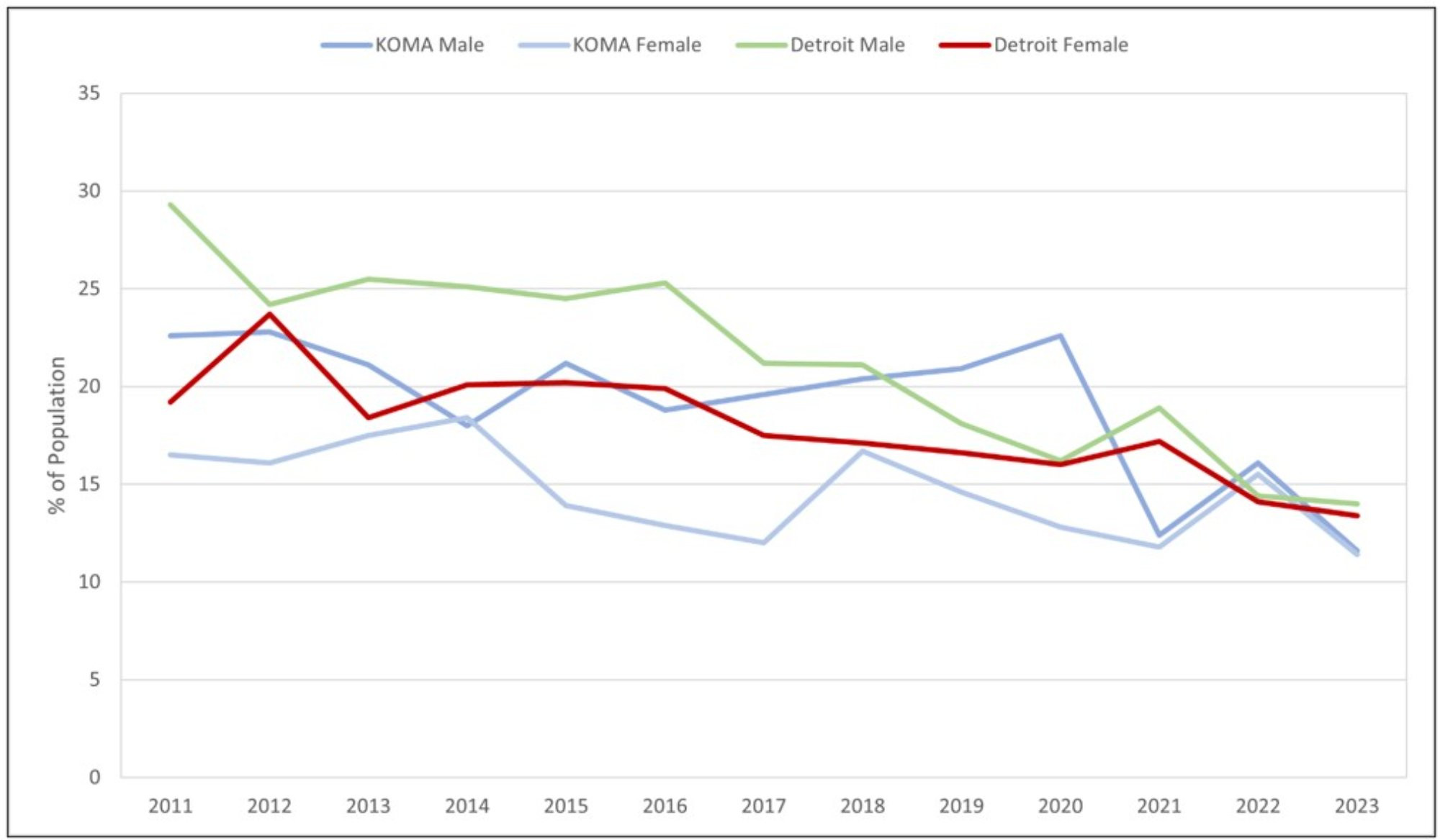

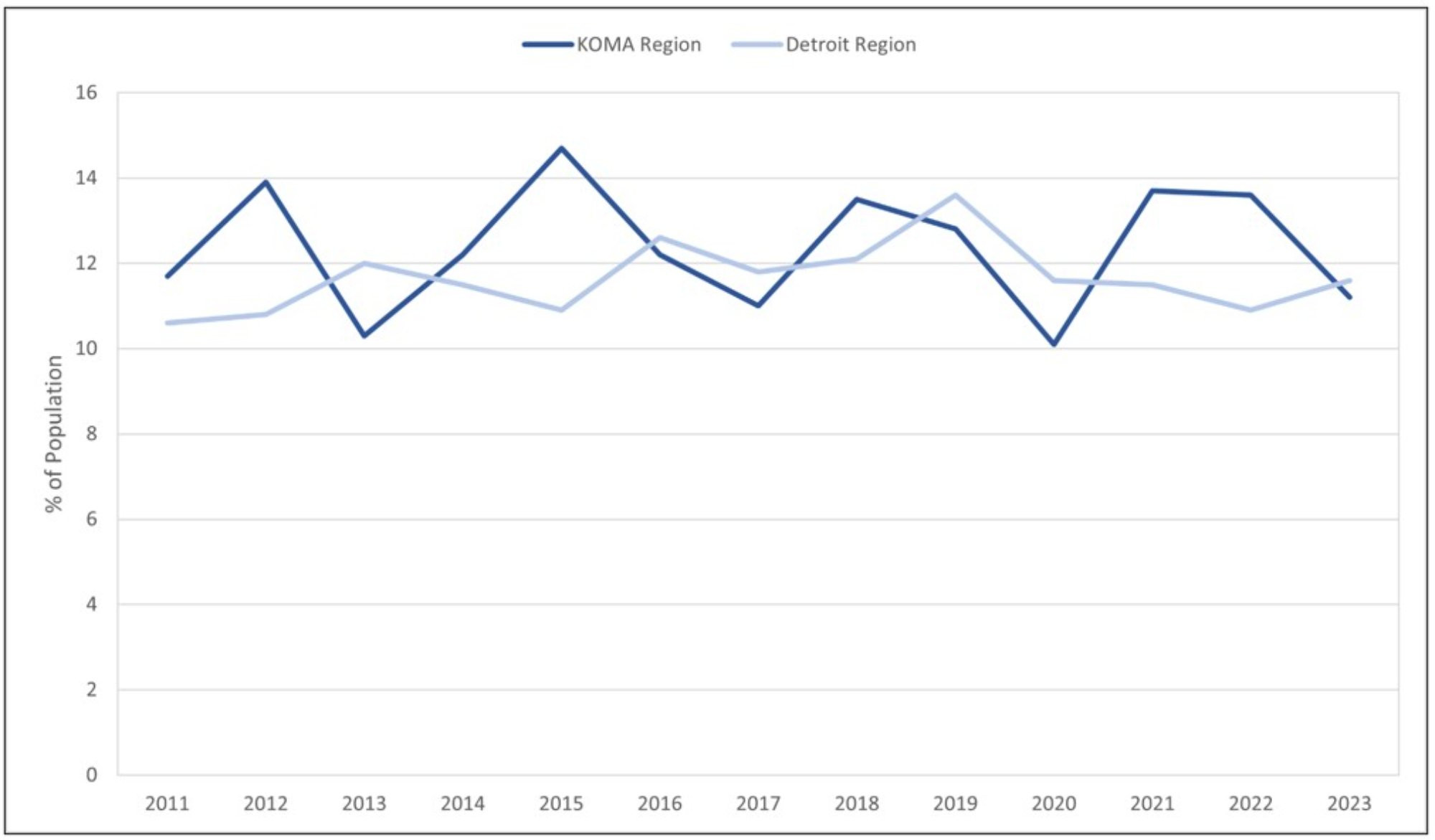

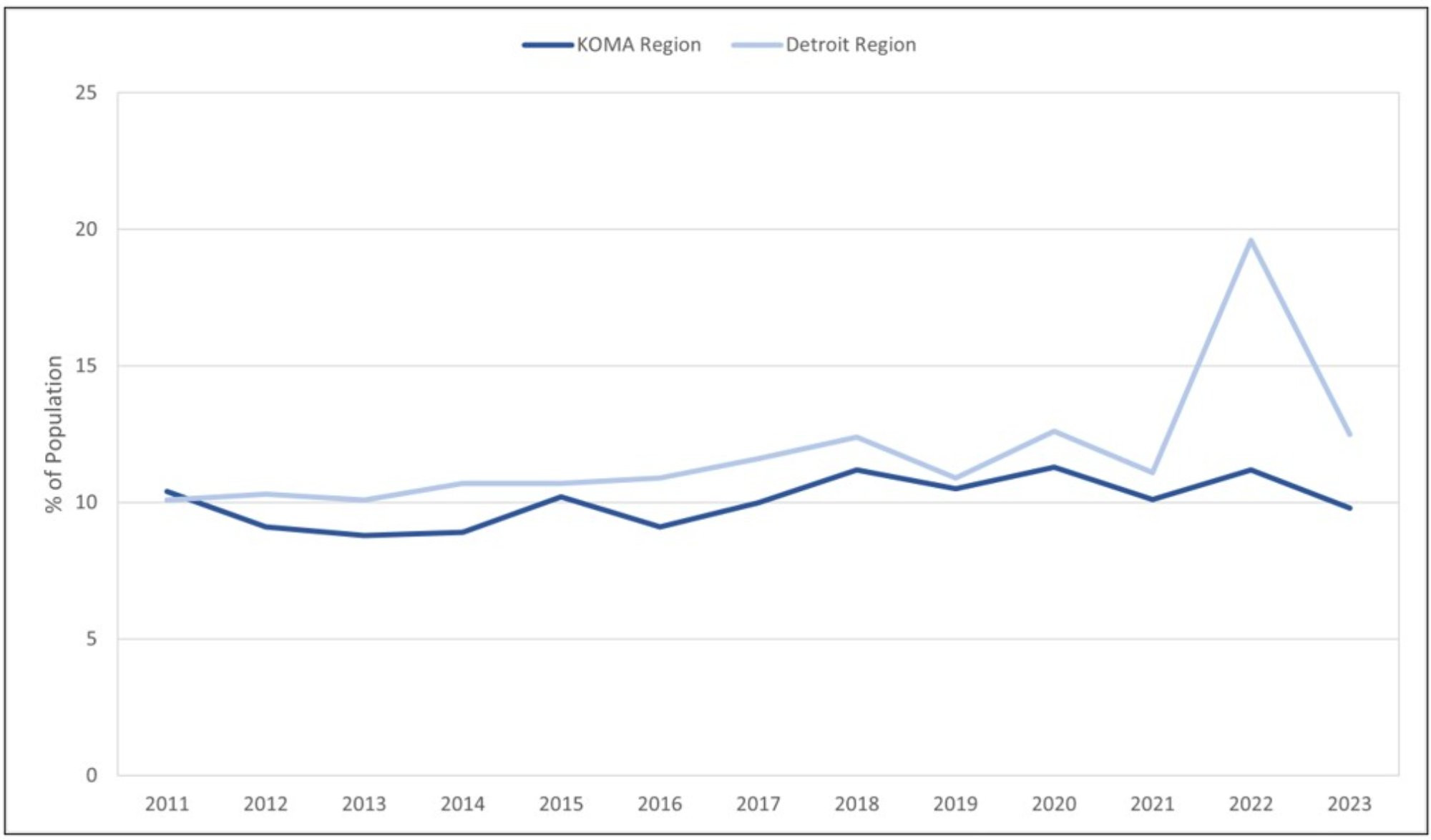

Figure 4 shows a consistent declining trend in forfeiting care due to cost for males and females in both regions. However, recent data suggests an upswing in the lack of care due to cost; KOMA women are the only demographic immune to this unfolding trend. For example, in Detroit, the proportion of males and females lacking care due to cost declined by approximately 10 percent between 2011 and 2022. Yet, compared to 2022, 2023 highlights a two and four-percent increase in unaffordable care among Detroit males and females, respectively. In West Michigan, both males and females found healthcare more affordable between 2011 and 2021, with a slight increase in unaffordable care observed after 2021. Compared to 2022, KOMA females are the only sample to have found care more affordable in 2023. Although the precise mechanism for alleviating the disparity in unaffordable care is ambiguous, the positive developments after 2019 may stem from the federal subsidies enacted during the COVID-19 pandemic. An exciting avenue for future research is to disentangle the causal effect of federal fiscal responses on healthcare access by race and gender during the pandemic.

Figure 4: No Health Care Access Due to Cost by Gender, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 4 displays the prevalence of those reporting no healthcare access by gender and region for cost-related reasons. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that no care due to costs has decreased by 28.2% in KOMA since 2011 but has increased by 25.3% since the COVID-19 pandemic. Similar trends have been found in all data strata.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

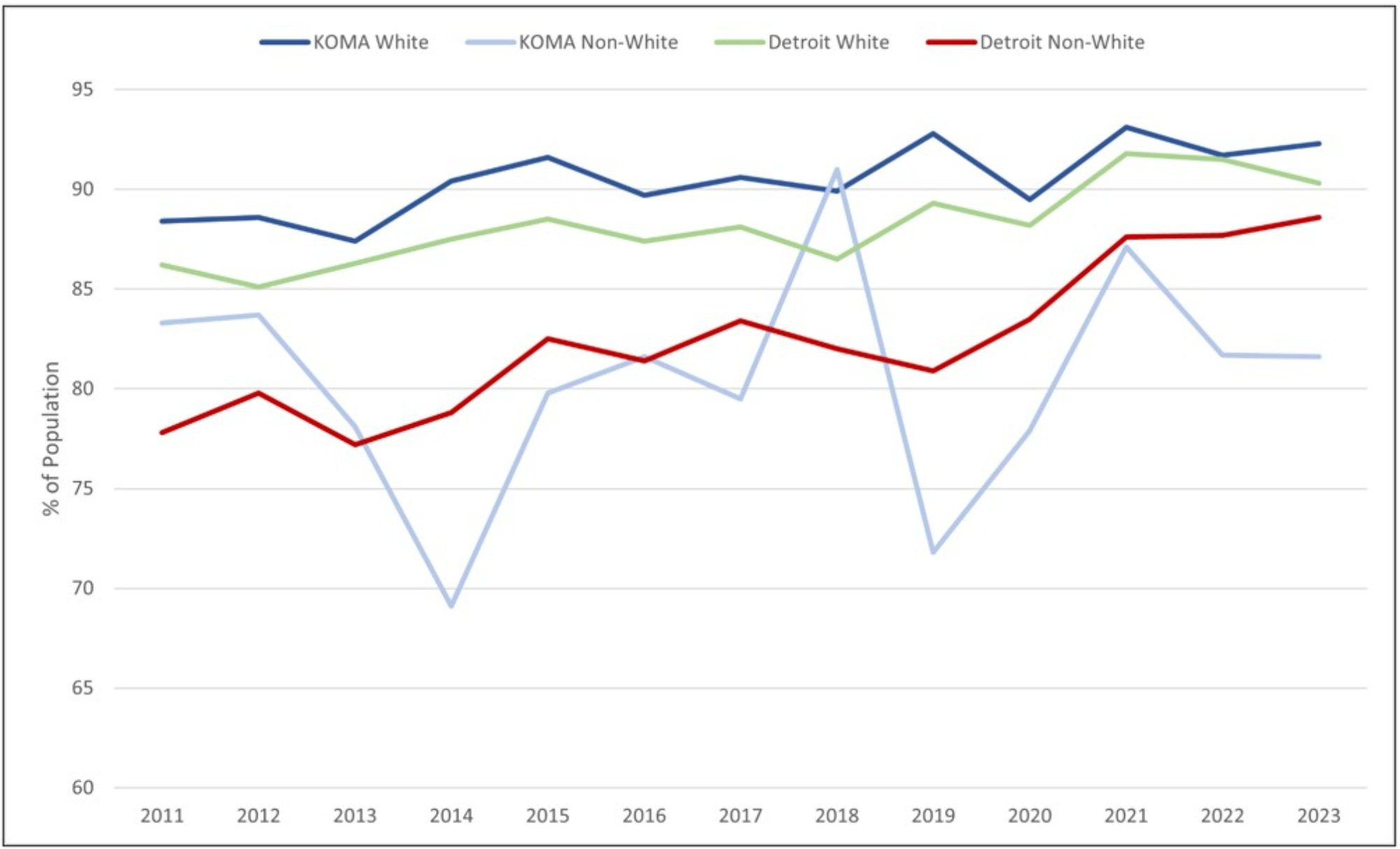

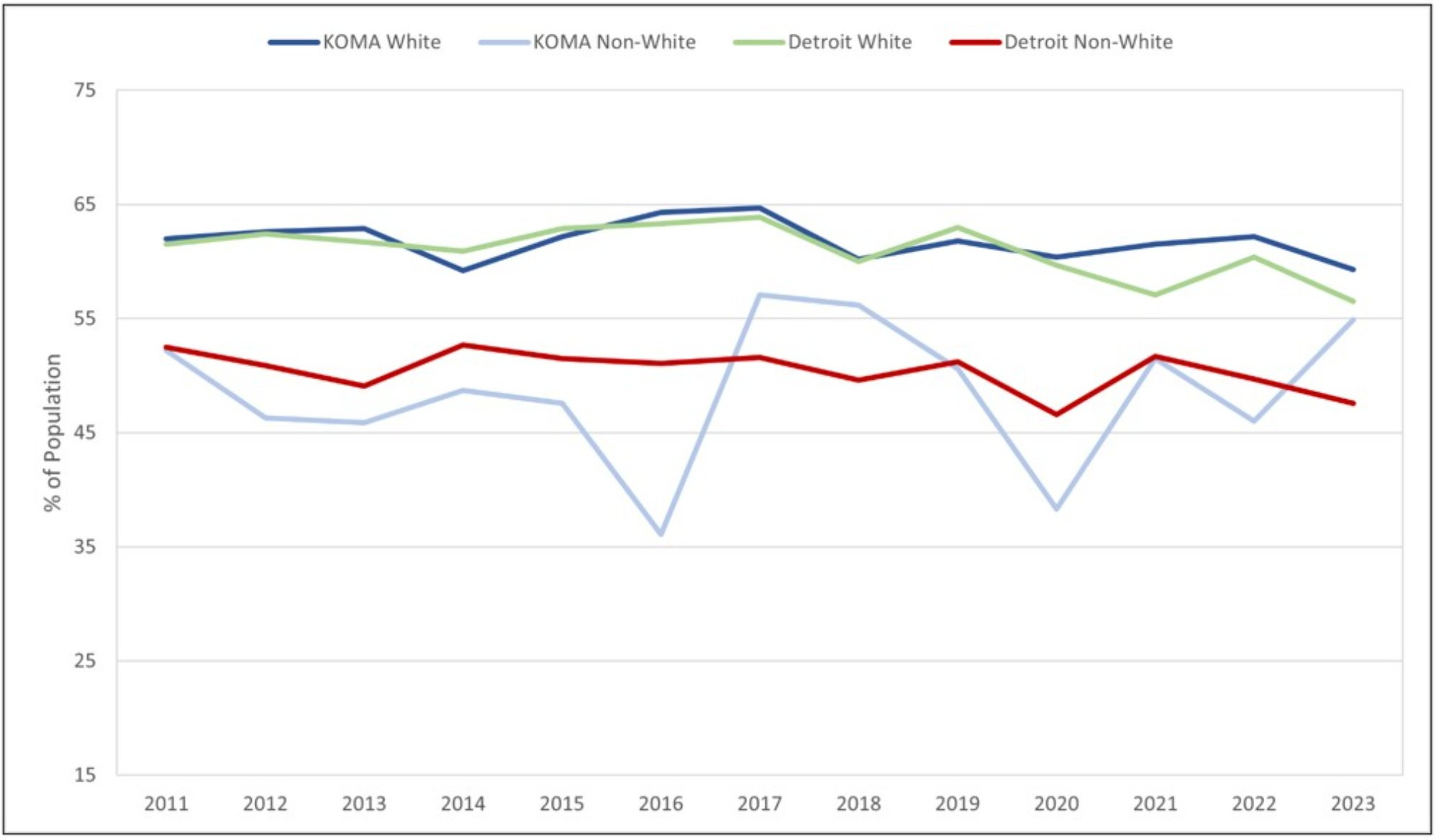

Figures 5 and 6 continue examining access to care by tracking the share of the population that reported having a usual source of care when ill. There are two notable observations. First, in Figure 5, we observe non-negligible disparities between non-white and white individuals in both regions, with the latter group being more likely to have a usual source of care. The trends in having a usual source of care are relatively stable over time, except for non-white KOMA residents, who exhibit higher variability. On average, non-white individuals in KOMA are less likely to have a usual source of care than their white counterparts. Furthermore, we find a widening gap between white and non-white residents in usual sources of care across West Michigan, which is not observed on the state’s east side.

Figure 5: Has a Usual Source of Care by Race, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 5 displays the prevalence of those reporting having a usual source of care by race and region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that care accessibility has increased by 4.5% and 4.9% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. Similar trends have been found in all data strata, except among KOMA non-white residents, which has decreased by 2% since 2011.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

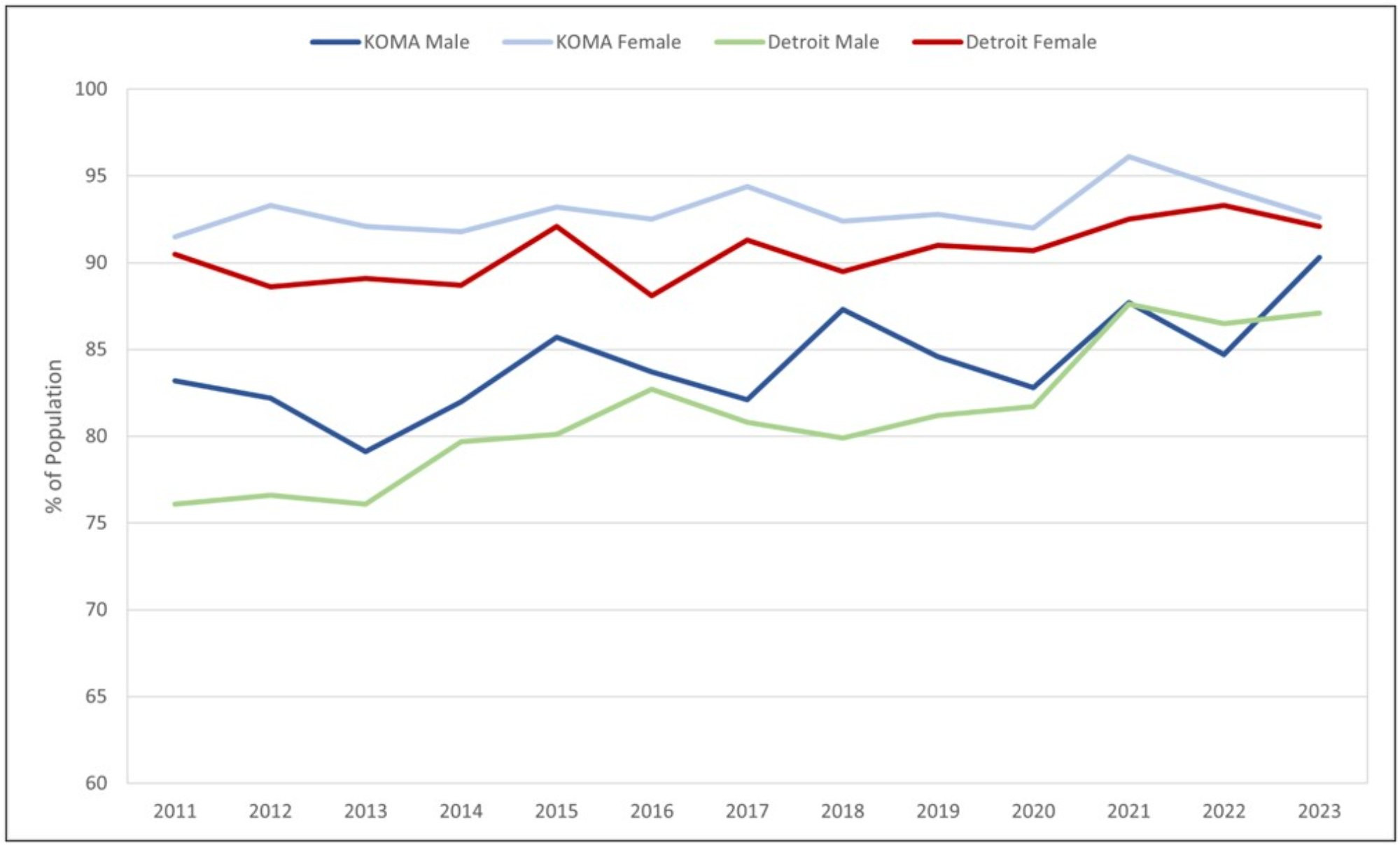

Secondly, Figure 6 shows a noticeable difference in care between genders. Specifically, the males in KOMA and Detroit report a lower likelihood of having a usual source of care. For instance, in 2023, 90 percent of KOMA men reported a typical source of care compared to 93 percent of women. Similarly, 92 percent of Detroit females reported a usual source of care, while only 87 percent of males agreed.

Figure 6: Has a Usual Source of Care by Gender, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 6 displays the prevalence of those reporting having a usual source of care by gender and region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that care accessibility has increased by 4.5% and 4.9% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. Similar trends have been found in all data strata.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

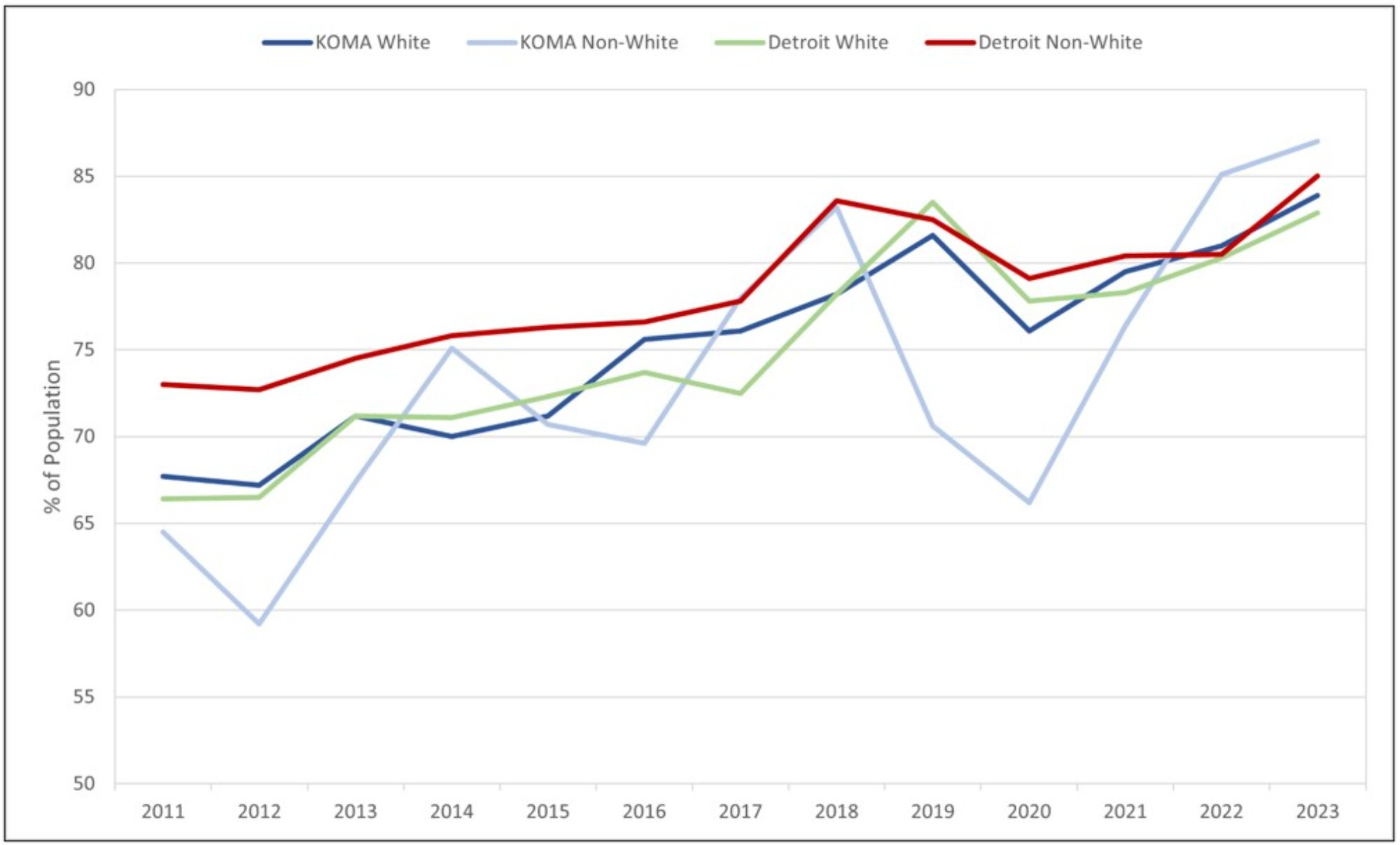

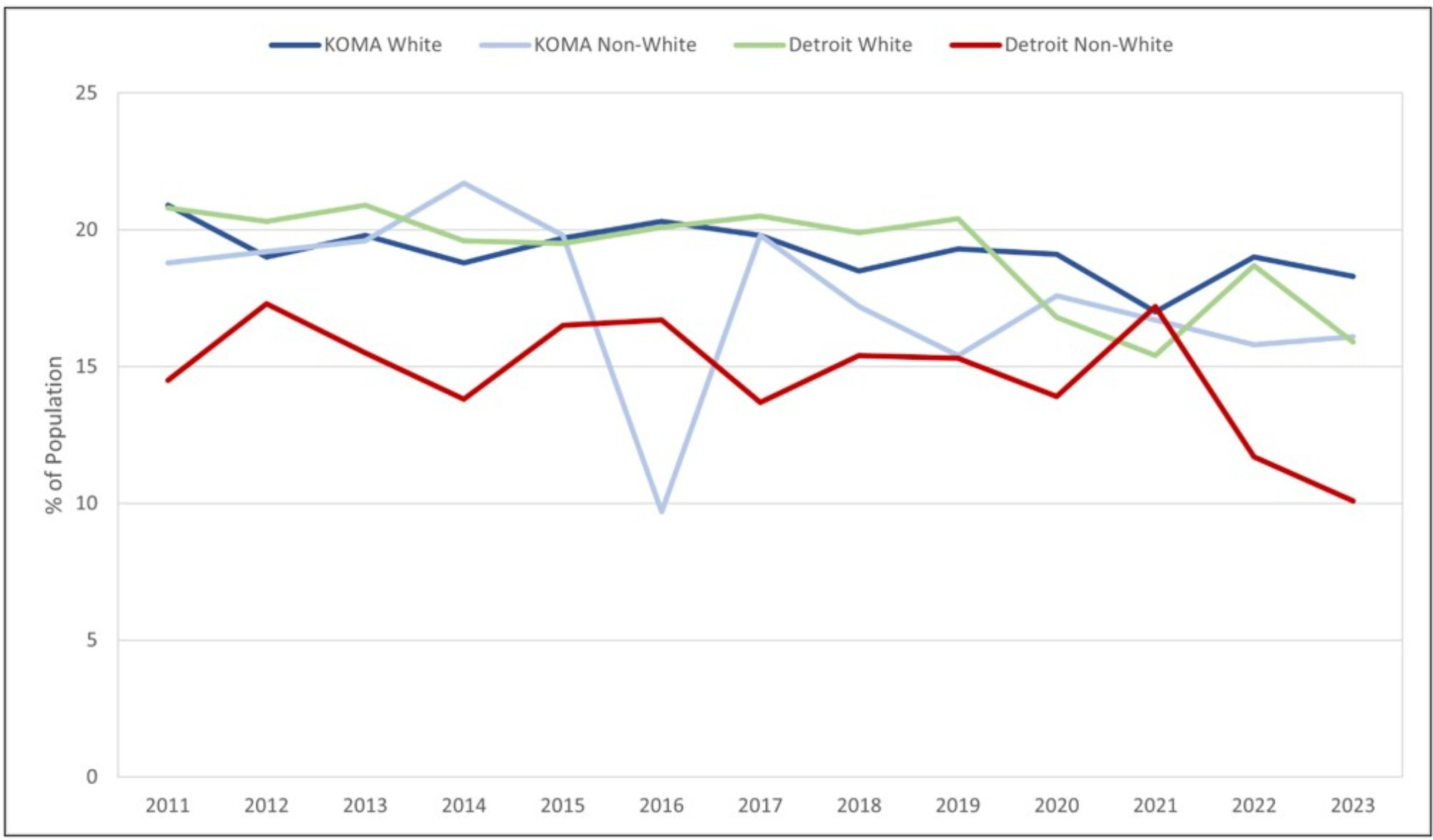

Lastly, Figures 7 and 8 plot the population share in East and West Michigan that had a routine checkup within the last year. Although earlier figures highlighted that healthcare access increased during the pandemic, these increases may have been driven by medical conditions related to COVID-19. An important concern during the pandemic was the increase in individuals delaying care for chronic conditions or avoiding preventive care due to the risk of virus exposure. Aslim et al. (2022) show that, during the pandemic, more than 30 percent of adults delayed medical care for conditions other than COVID-19. Our findings in Figures 7 and 8 are consistent with the existing literature.

Figure 7: Had Routine Checkup in Past Year by Race, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 7 displays the prevalence of those reporting having had a routine checkup in the last year by race and region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that checkups have increased by 24.4% and 12.8% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. Similar trends have been found in all data strata.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

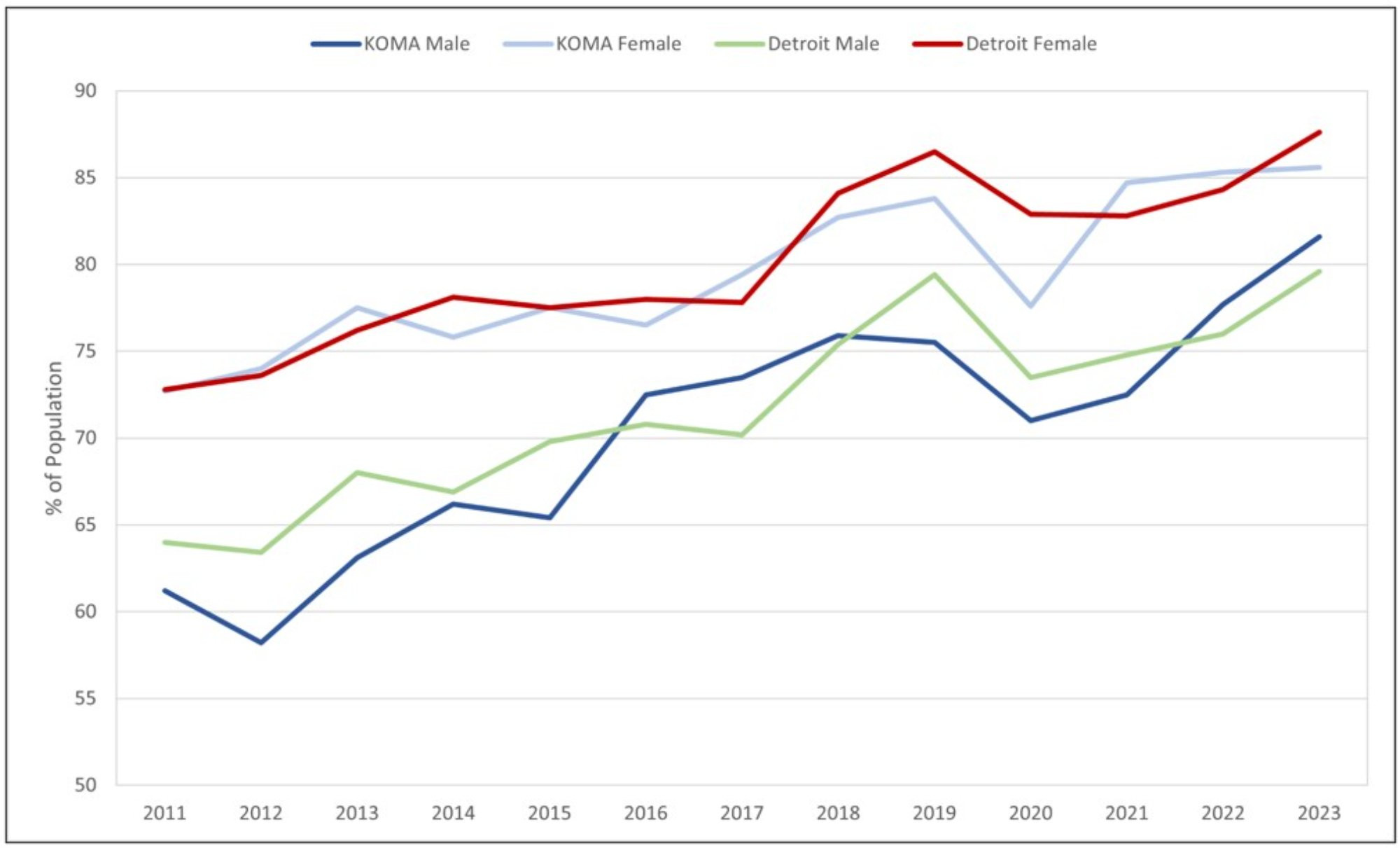

Figure 8: Had Routine Checkup in Past Year by Gender, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 8 displays the prevalence of those reporting having had a routine checkup in the last year by gender and region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that checkups have increased by 24.4% and 12.8% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. Similar trends have been found in all data strata.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

Although there was an increase in routine checkups until 2019, we observed a sharp decline in routine checkups in 2020. This is particularly problematic because delaying care for treatable and preventable conditions may lead to an increase in avoidable deaths, whether directly or indirectly related to the pandemic.

A critical finding in the literature is that receiving the COVID-19 vaccination reduces concerns about spreading or contracting coronavirus, reducing the likelihood of delaying care (Aslim et al., 2022). It is important to note that the COVID-19 vaccine was rolled out across states in 2021. Consistent with the vaccine, we observed a sharp increase in routine checkups for white and non-white individuals in both regions. This finding corroborates the view that the COVID-19 vaccine may have incentivized individuals to seek preventative care.

Pairing Figure 8 with the previous figures highlights disparities in healthcare access, including access to routine checkups, a larger problem among males than females. Healthcare providers and public health organizations should continue stressing the importance of preventative care through annual exams to promote education and help monitor high-health risk-related behaviors.

An important takeaway from this section is that substantial racial disparities in health insurance and healthcare access still persist in KOMA. These disparities underscore the urgent need for policy interventions to reduce these inequities. Potential strategies may include improved outreach efforts for health insurance enrollment, fostering greater diversity among healthcare staff, and implementing targeted programs to address the unique healthcare needs of underserved communities.

The following section delves into general and mental health trends, exploring how these indicators may naturally change in response to health insurance and healthcare access shifts.

General Health and Mental Health

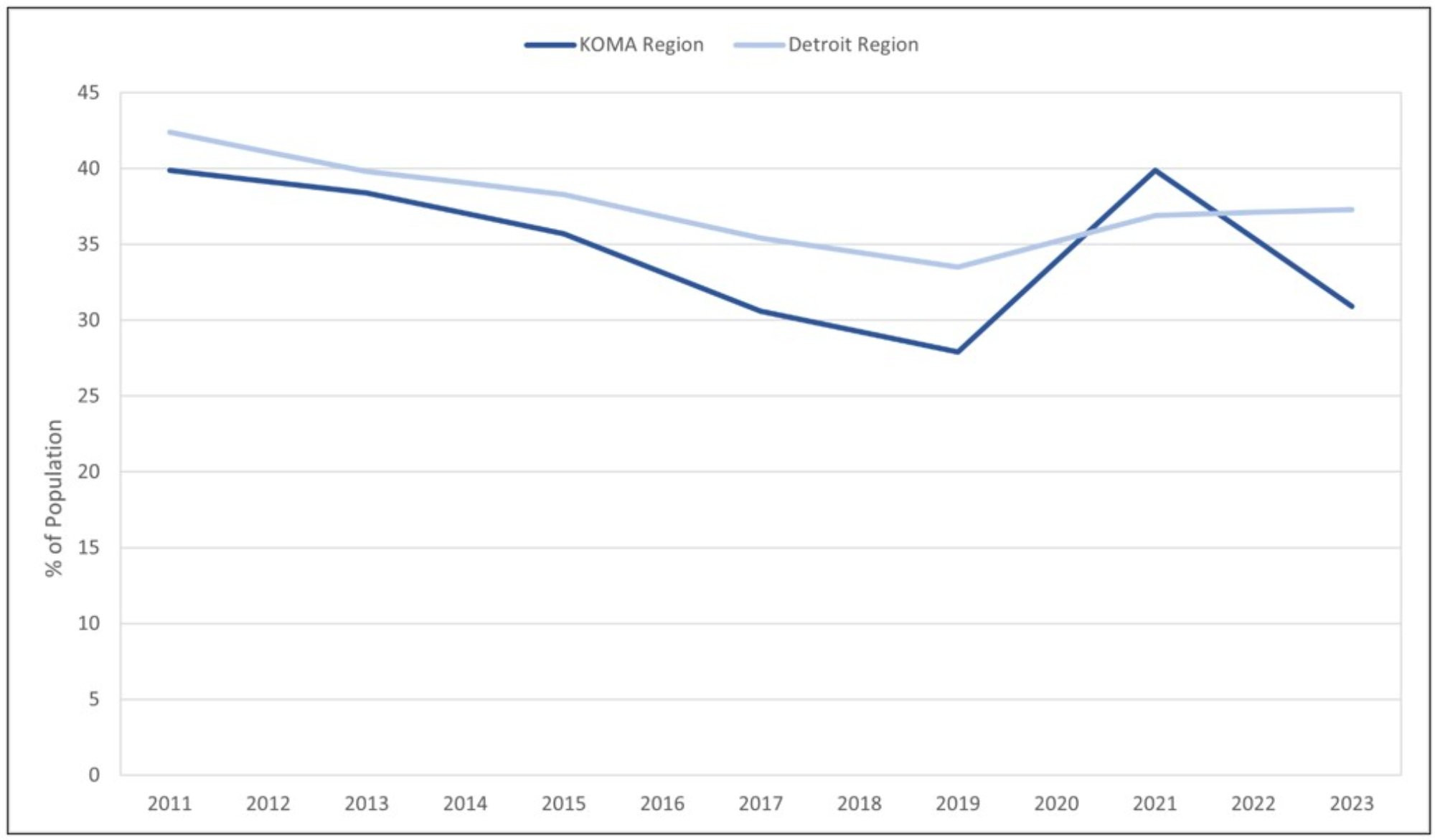

Figure 9 plots the share of the population reporting “fair” or “poor” health by race in KOMA and Detroit. In both locations, non-white populations are more likely to report fair or poor health. As a result, a noteworthy gap exists in the health status of non-white and white populations. However, the gaps in both regions appear to be getting smaller in time. For example, the gap between non-white and white residents has decreased from 16 percent to 5 percent in KOMA between 2011 and 2023. While a shrinking gap is less noticeable in East Michigan, and the rate of decrease is considerably lower compared to KOMA, the racial gap in Detroit has still managed to fall by two percent over the same period, with non-white residents still reporting a larger percentage of poor health days.

A second emerging trend is the decrease in fair or poor health statuses observed in KOMA compared to the recent increase in fair or poor health reported in Detroit. West Michigan white and non-white residents reported better health in 2023, with fair or poor health measures down by one percent. Meanwhile, a corresponding increase in fair or poor health was reported in Detroit for white and non-white citizens alike, with a noticeable rise occurring among white residents from 13 percent to 18 percent during 2022 and 2023.

Figure 9: Health Status - Fair or Poor by Race, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 9 displays the prevalence of those reporting having fair or poor health by race and region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that fair or poor health has decreased and increased by 3.5% and 3.0% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. Mixed trends have been found in all data strata.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

Figure 10 highlights different fair or poor health trends by gender and region. However, recent data indicates that within each locality, a gender convergence in fair or poor health is underway. For example, the 2023 gender gap in poor health is less than one percent in both regions. However, the divergence between East and West Michigan is more noticeable. Between 2022 and 2023, Detroit observed an increase in persons reporting fair or poor health, with both genders responsible for the growth in poor health. Conversely, over the same period, KOMA observed a decrease in fair or poor health despite the slight increase in poor health reported by men. As a result, the regional disparity in poor health has increased from 2 percent in 2022 to 6 percent in 2023.

Figure 10: Health Status – Fair or Poor by Gender, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 10 displays the prevalence of those reporting having fair or poor health by gender and region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that fair or poor health has decreased and increased by 3.5% and 3.0% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. Similar trends have been found in all data strata.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

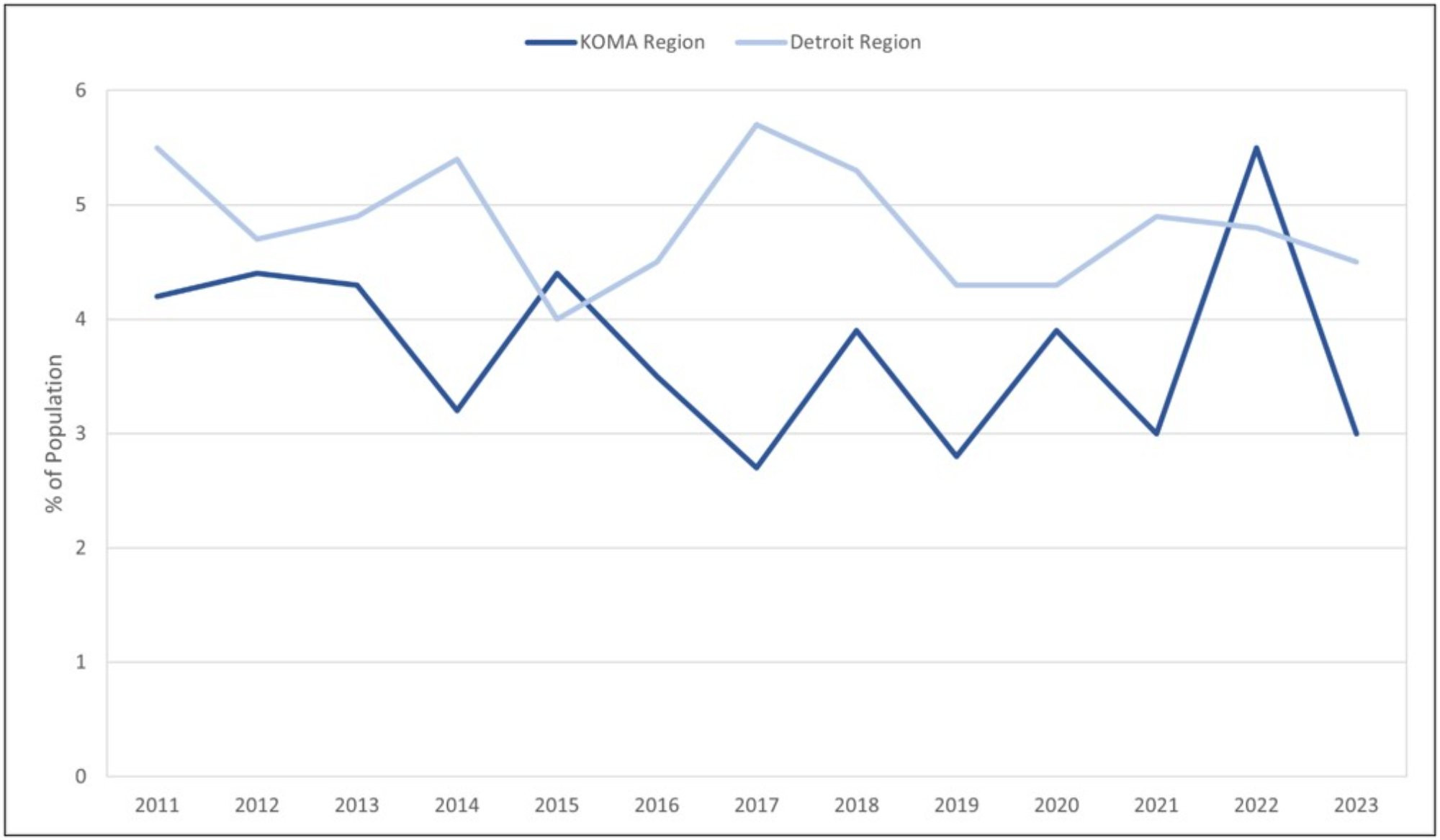

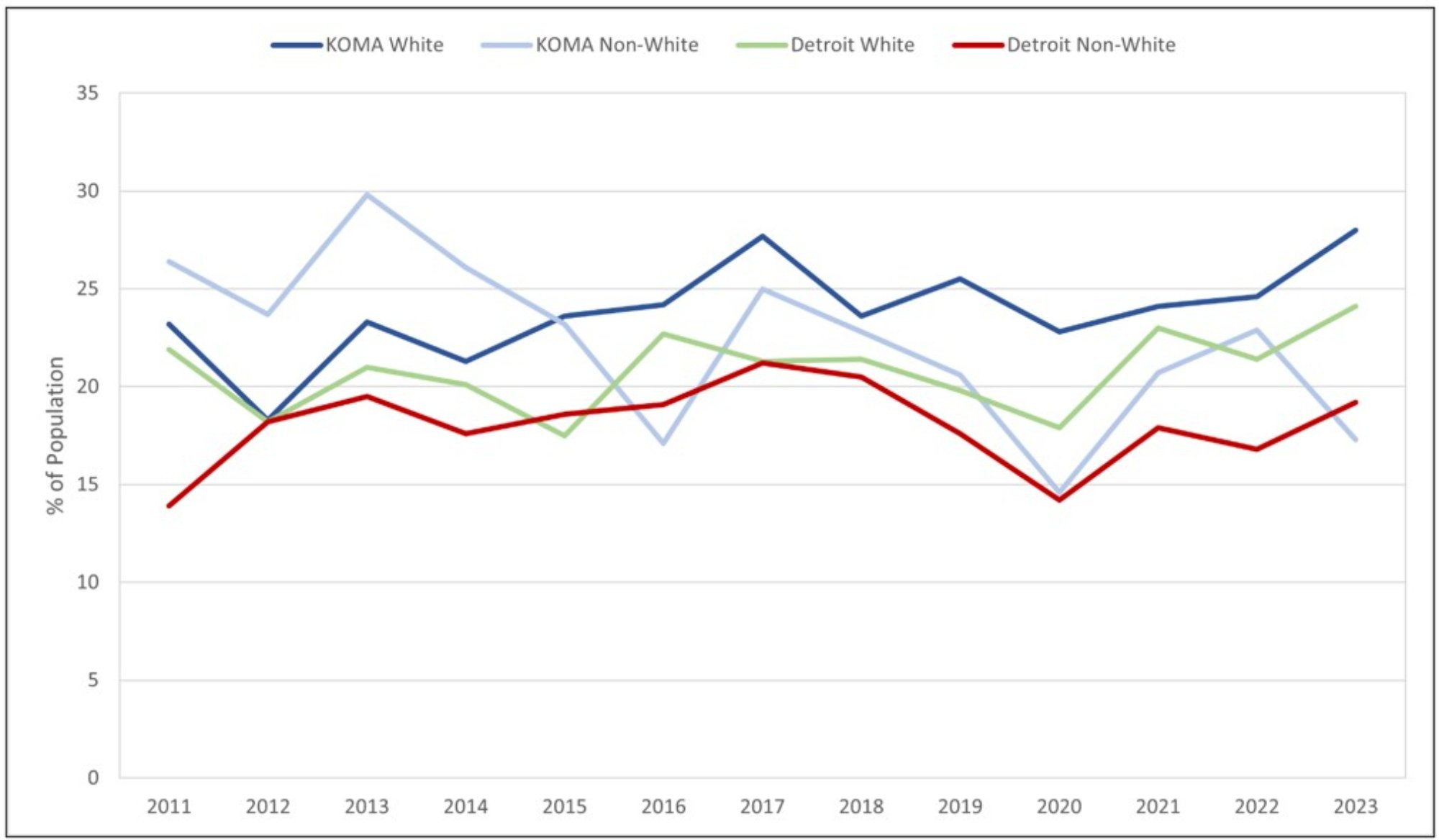

Figure 11 reports the fraction of white and non-white survey respondents who reported experiencing more than 14 days of poor mental health within the last month. A clear disparity exists when analyzing mental health by race and region. On average, non-white residents report poorer mental health compared to white residents in both localities. Before the pandemic, the racial gap in poor mental health remained stable at an average of 5 percent in KOMA, with non-white residents disproportionately reporting worse mental health outcomes. In Detroit, the pre-pandemic racial gap stood at an average of 2 percent. However, since the pandemic, the average racial gap has expanded to 7 percent in KOMA and disappeared in Detroit. The recent changes in poor mental health are starker in KOMA compared to Detroit. In 2022, the poor mental health gap between the non-white and white residents of KOMA stood at 2 percent. By 2023, that racial gap expanded in KOMA to 11 percent.

Figure 11: Poor Mental Health Days by Race, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 11 displays the prevalence of those reporting having had 14 or more poor mental health days in the last month by race and region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that poor mental health has increased by 7.6% and 10.1% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. However, trends differ by race, with non-whites reporting more depression and whites reporting less.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

Figure 12 analyzes poor mental health by gender and region. Again, a disparity in poor mental health exists when segmenting the data by gender. Regardless of geography, women disproportionately report poorer mental health compared to men. Accounting for Figure 11, the increase in poor mental health that is observed among non-white KOMA residents appears primarily driven by females. The average gender gap in poor mental health increased in KOMA and Detroit by 2 percent and 3 percent pre and post-pandemic, respectively. However, between 2022 and 2023, the fraction of women reporting poor mental health in KOMA has decreased from 21 percent to 15 percent.

Figure 12: Poor Mental Health Days by Gender, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 12 displays the prevalence of those reporting having had 14 or more poor mental health days in the last month by gender and region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that poor mental health has increased by 7.6% and 10.1% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. However, trends differ by gender, with males reporting more depression and females reporting less.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

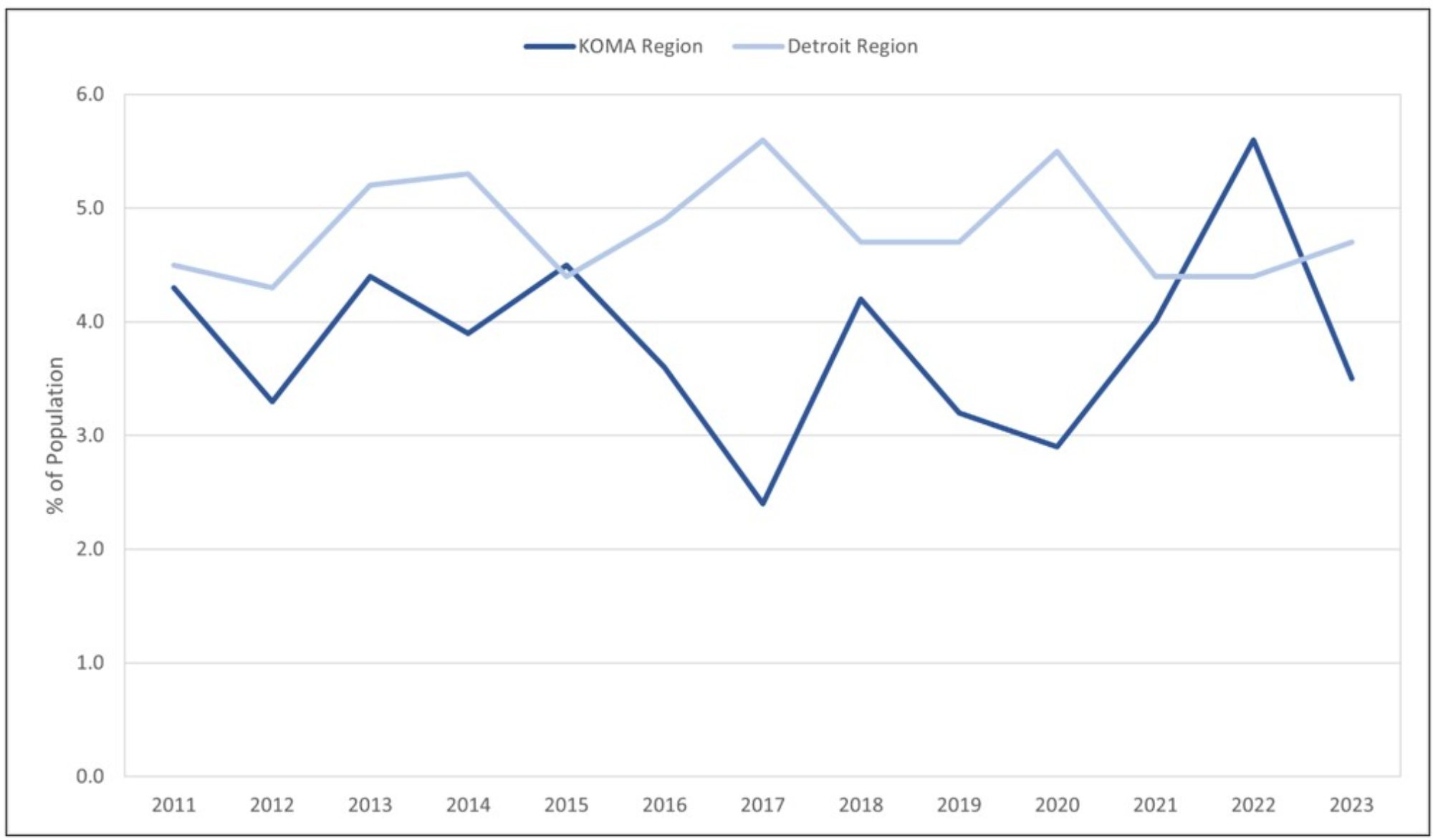

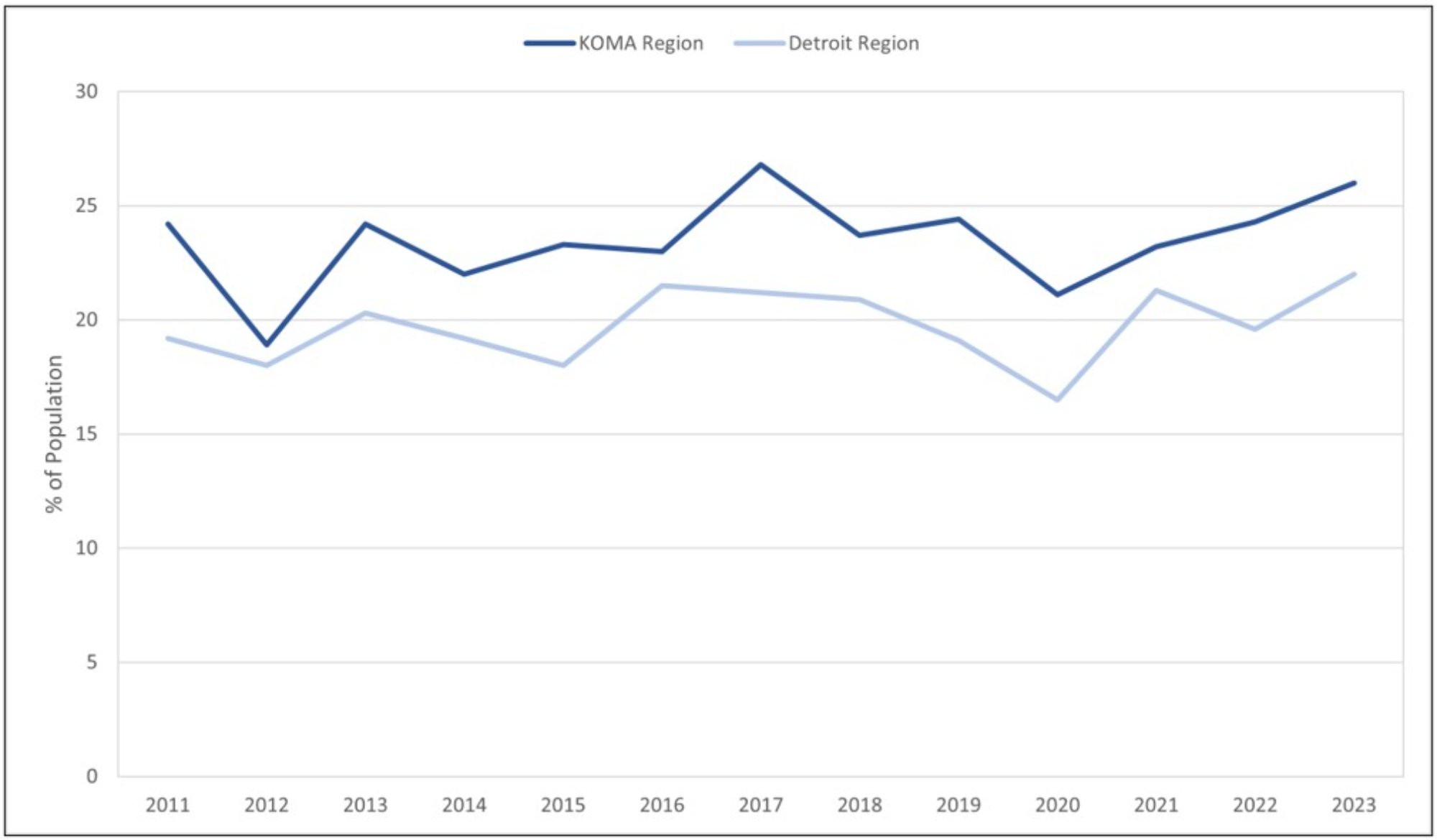

Figures 13 and 14 track the prevalence of obesity by race and gender in East and West Michigan. Individuals are considered obese if their Body Mass Index (BMI) exceeds 30. On average, a racial gap exists between the non-white and white populations in both localities, with non-white obesity rates exceeding white obesity rates between 2011 and 2023 (see Figure 13). In KOMA and Detroit, the average racial gap between non-white and white obesity averages 4 percent and 7 percent, respectively. In KOMA, the non-white population exhibits considerable variability in reported obesity when compared to their white counterparts. For example, both pre- and post-pandemic, we find an average white obesity in KOMA of 29 percent, respectively. However, during the same periods, non-white obesity in KOMA has increased from 33 percent to 36 percent.

Figure 13: Obesity by Race, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 13 displays the prevalence of those reporting obesity by race and region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that obesity has increased by 19.1% and 2.4% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. Similar trends are found in all data strata.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

Turning to the most recent data, we find an increase in the racial gap of KOMA obesity. Between 2022 and 2023, non-white obesity in KOMA has increased from 31 percent to 40 percent, while white obesity in KOMA has decreased from 36 percent to 31 percent. Meanwhile, both non-white and white obesity rates have recently increased in Detroit. Looking at the recent increases in obesity, it remains imperative to monitor obesity trends among Michigan residents in future reports, as studies indicate that healthcare costs associated with obesity account for 10 percent to 20 percent of total U.S. healthcare spending (Cawley & Meyerhoefer, 2012; Finkelstein et al., 2009).

Gender differences in obesity are presented in Figure 14. Regardless of gender, we observe an increase in obesity among KOMA and Detroit residents between 2011 and 2023. In KOMA, we find an increase in obesity among males and females, with men exhibiting a stronger incline over time. For example, between 2011 and 2023, obesity among KOMA men and women increased by 7 percent and 4 percent, respectively. In recent data, between 2022 and 2023, KOMA males saw an increase in reported obesity from 33 percent to 34 percent, while KOMA females saw a decrease in obesity from 38 percent to 34 percent.

A different story emerges in Detroit. Not only has Detroit obesity by gender increased throughout this study, but recent data highlights a further increase in obesity, especially among Detroit women. Of concern, Detroit women have officially reported a historical high in the fraction of obese persons (38 percent in 2023). Between 2011 and 2023, male and female obesity in Detroit has increased by 7 percent. As a result, taking race and gender together, KOMA has observed a slight decrease in obesity between 2022 and 2023, from 35 percent to 34 percent. Meanwhile, Detroit has observed an increase in obesity from 34 percent to 36 percent. If these trends persist, East Michigan will continue to face a more significant obesity problem compared to West Michigan. Because the medical cost of obesity is high, regardless of location, obesity remains a problem to continuously monitor for future healthcare planning.

Figure 14: Obesity by Gender, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 14 displays the prevalence of those reporting obesity by gender and region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that obesity has increased by 19.1% and 2.4% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. Similar trends are found in all data strata.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

In Figures 15 and 16, we report the fraction of alcohol consumers by gender and race in KOMA and Detroit. An instance of alcohol consumption is defined as anyone who consumes alcohol within the prior month. Therefore, the proportion of alcohol consumers is derived by comparing the number of persons who meet the alcohol consumption criteria to the number of survey respondents within each locality. Figure 15 focuses on alcohol consumption by race in both regions. A clear distinction is drawn between white and non-white persons, with the former reporting more alcohol consumption in KOMA and Detroit. For example, the white-to-non-white gap in alcohol consumption averaged 13 percent and 11 percent in KOMA and Detroit between 2011 and 2023. However, in a trend not matched by KOMA, Detroit’s racial gap has decreased since the start of the pandemic. Before the pandemic, the racial gap in Detroit’s alcohol consumption averaged 11 percent between white and non-white residents. Since 2020, that gap has decreased by one percent. In recent years, each region has told a different story on the racial changes in alcohol consumption. Between 2022 and 2023, the gap between white and non-white alcohol consumers has fallen by 12 percent in KOMA; in Detroit, that gap has only shrunk by two percent.

Figure 15: Alcohol Consumption by Race, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 15 displays the prevalence of those reporting having had alcohol in the last month by race and region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that alcohol consumption has decreased and increased by 3.5% and 3.0% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. Similar trends are found in all data strata, with a significant spike in non-white drinking since 2020.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

In Figure 16, we focus on alcohol consumption by gender, with men disproportionally reporting higher rates of alcohol consumption despite locality. On average, KOMA men report 8 percent more cases of alcohol consumption compared to women spanning 2011 to 2023. A similar gender gap exists in Detroit (an average of 10 percent) over the same period. However, the gap in male-to-female alcohol consumption has decreased by 2 percent and 3 percent following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in KOMA and Detroit. The recent trends in the gender drinking gap are of interest. Between 2022 and 2023, the male-to-female alcohol consumption gap has decreased from 14 percent to 7 percent in KOMA; this decrease has resulted from a significant decrease in male consumption and a corresponding rise in female alcohol consumption. Meanwhile, over the same period, Detroit has witnessed an increase in the gender alcohol consumption gap from 6 percent in 2022 to 10 percent in 2023.

Figure 16: Alcohol Consumption by Gender, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 16 displays the prevalence of those reporting having had alcohol in the last month by gender and region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that alcohol consumption has decreased and increased by 3.5% and 3.0% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. However, females typically report lower rates of consumption compared to males.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

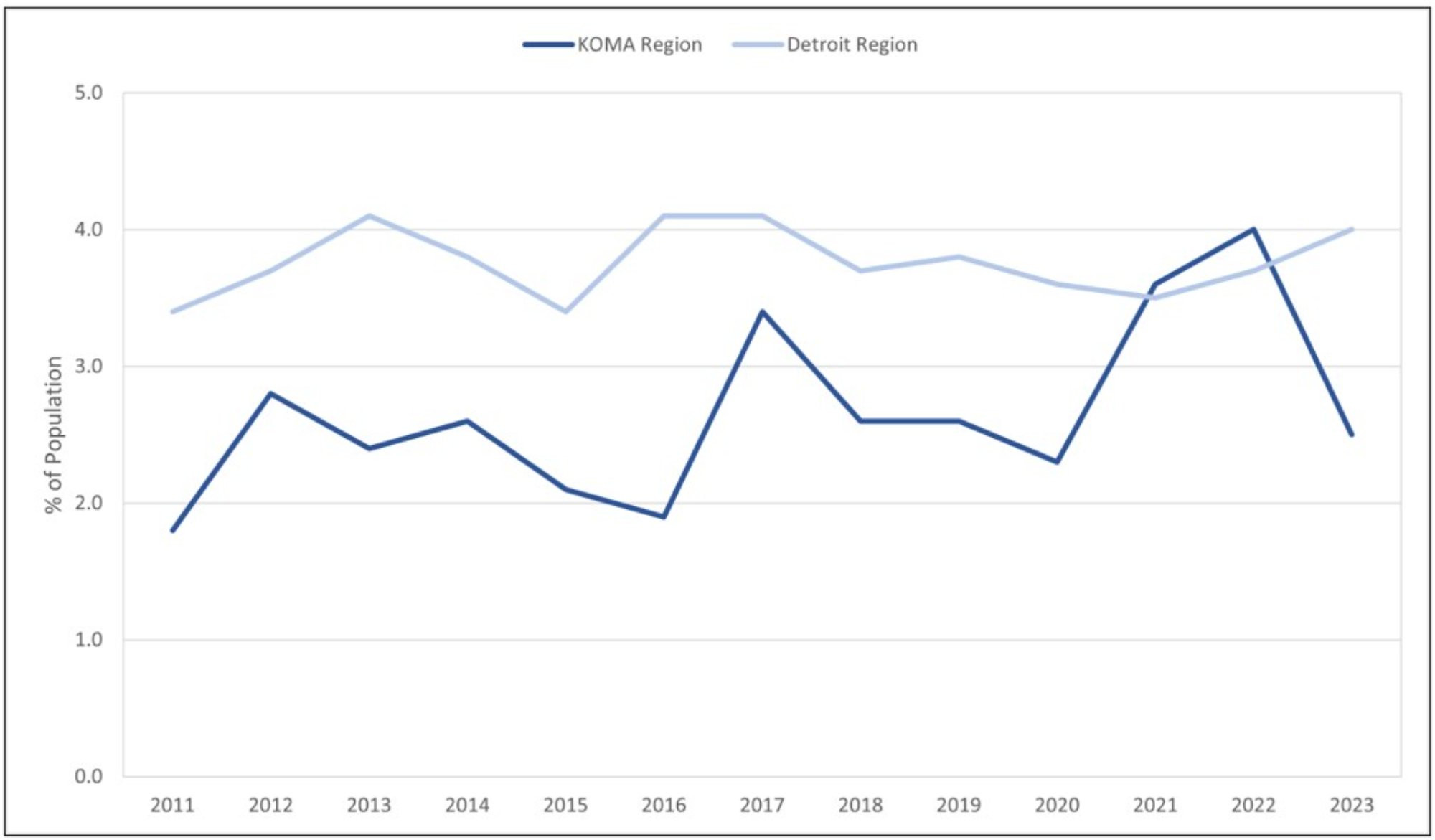

Now, because the definition of alcohol consumption is rather strict, we turn to cases of binge drinking. Figure 17 presents the estimates of binge drinking among the white and non-white residents in KOMA and Detroit. Binge drinking is defined as the consumption of four or more drinks on a single occasion for women and five or more drinks on a single occasion for men. A racial disparity exists in binge drinking, with white persons repeatedly reporting more episodes of excessive drinking in both localities. For example, between 2011 and 2023, the racial gap between white and non-white binge drinkers averaged 2 percent and 4 percent in KOMA and Detroit, respectively.

Figure 17: Binge Drinking by Race, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 17 displays the prevalence of those reporting binge drinking in the last month by race and region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that binge drinking has decreased by 10.8% and 4.2% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. Similar findings are found across all data strata.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

Figure 18 submits a gender comparison of binge drinking for East and West Michigan residents. Regardless of location, men are disproportionally more likely to report instances of excessive drinking within the prior month. On average, between 2011 and 2023, the gender gap in male-to-female binge drinking stands at 10 percent and 8 percent in KOMA and Detroit. However, a promising trend has appeared in male binge-drinking episodes in both localities since the start of the pandemic. For example, comparing pre to post-pandemic averages suggests that male binge drinking has decreased by 3 percent in KOMA and 5 percent in Detroit. Meanwhile, female binge drinking has largely remained unchanged during these periods. As a result, we have observed a decrease in the gender drinking gap between 2011 and 2023 in both regions.

Taking race and gender together, the fraction of binge drinkers in KOMA and Detroit has fallen between 2011 and 2023. However, more recently, the regional gap in binge drinking has widened, with more binge drinking reported in KOMA compared to Detroit. Between 2022 and 2023, the proportion of binge drinkers has fallen by 2 percent in Detroit and 1 percent in KOMA. Meanwhile, the regional gap in binge drinking between KOMA and Detroit has widened from 2 percent in 2022 to 5 percent in 2023. In historical context, the regional gap in binge drinking is currently the highest out of any year analyzed since 2011, with higher rates of binge drinking reported in KOMA residents.

Figure 18: Binge Drinking by Gender, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 18 displays the prevalence of those reporting binge drinking in the last month by gender and region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that binge drinking has decreased by 10.8% and 4.2% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. Similar findings are found in males, while females report higher rates of binge drinking.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

In Figures 19 and 20, we turn to the prevalence of smoking by race and gender in the KOMA and Detroit regions. Figure 19 presents the estimates for the proportion of white and non-white citizens who are current cigarette smokers. A few notable trends emerge in the data. Firstly, non-white persons are more likely to report cigarette use in both locations. On average, non-white persons report 6 percent more instances of smoking than white persons in KOMA and 3 percent more in Detroit between 2011 and 2023. Secondly, since 2020, the racial gap between non-white and white smoking has decreased by an average of 3 percent in both regions. However, if we focus on the changes in smoking between 2022 and 2023, it paints a different story. Recently, the racial gap in smoking has increased in both East and West Michigan, where more instances of non-white smoking and fewer instances of white smoking primarily drive the increased gap. For example, between 2022 and 2023, white smoking decreased from 15 percent to 12 percent in Detroit. During the same period, the number of non-white smokers increased from 13 percent to 16 percent.

Figure 19: Current Cigarette Smokers by Race, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 19 displays the prevalence of those reporting smoking cigarettes in the last month by race and region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that smoking has decreased by 40.7% and 35.8% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. Similar findings are found in all data strata, except non-whites report higher rates of smoking since 2011.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

The gender composition of current smokers is presented in Figure 20. Taking the sample in its entirety highlights a decrease in smoking regardless of gender and location. On average, between 2011 and 2023, smoking prevalence has decreased by 10 percent across all genders and regions. However, despite the declining trend in smoking, men are still more likely to report instances of smoking in KOMA and Detroit. On average, between 2011 and 2023, we find that 4 percent more men report cases of smoking in KOMA compared to women. In Detroit, that same gap stands at 3 percent. However, since the start of the pandemic, the gender gap in smoking has declined in both regions. As of 2023, there is no longer a discernable smoking gap by gender among KOMA residents.

Despite a negligible difference in the gender composition of smoking, any non-zero reported smoking metric is still of concern. For example, the Centers for Disease Control (2022) still lists tobacco as the leading cause of disease and death in the United States. Treating illnesses related to tobacco use is costly and resource-intensive. Reducing smoking prevalence can boost worker productivity and help alleviate burgeoning healthcare expenditures (Berman et al., 2014).

Figure 20: Current Cigarette Smokers by Gender, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 20 displays the prevalence of those reporting smoking cigarettes in the last month by gender and region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that smoking has decreased by 40.7% and 35.8% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. Similar findings are found in all data strata.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

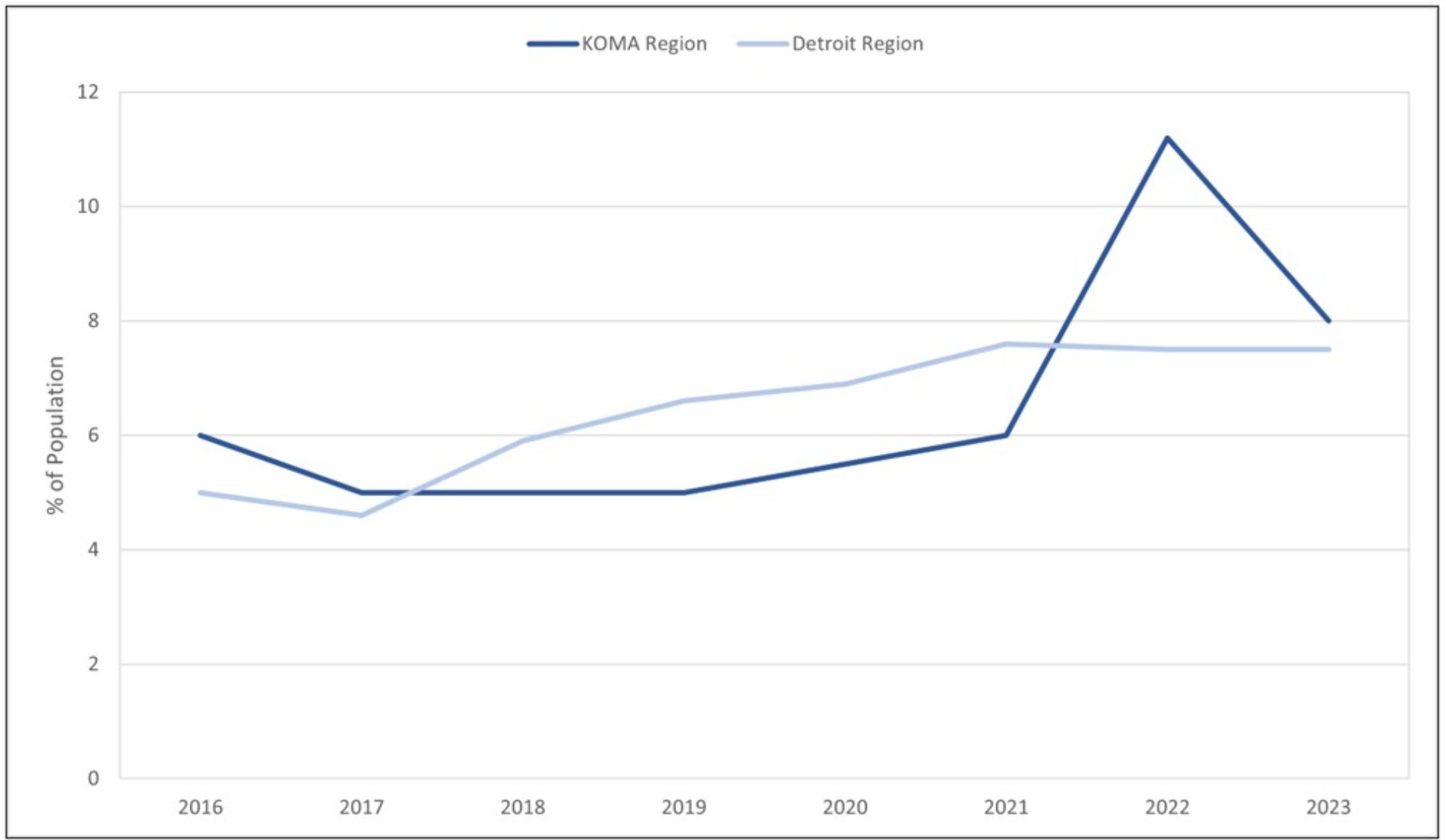

While Figure 20 highlights a declining trend in the percentage of cigarette smokers, there is a valid concern regarding whether this trend is driven by individuals who quit smoking altogether or substitute cigarette use with alternative tobacco products such as e-cigarettes. As a result, Figure 21 presents data on current e-cigarette use in both regions to analyze the substitutability between cigarettes and e-cigarettes. Between 2016 and 2023, the prevalence of e-cigarette use has increased in KOMA and Detroit. For example, in KOMA, e-cigarette usage increased from 6 percent in 2016 to 8 percent in 2023. A comparable increase is observed in Detroit during the same period.

Figure 21: Current E-Cigarette Use by Region, 2016-2023

Description: Figure 21 displays the prevalence of those reporting smoking e-cigarettes in the last month by region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that e-smoking has increased by 33.3% and 45.5% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. Similar findings are found in both regions.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2016-2023

Taken together, Figures 19 through 21 highlight the substitution from traditional tobacco products to e-cigarettes. However, it is important to emphasize that the MiBRFSS data exclusively encompasses the noninstitutionalized adult population. As a result, the data analyzed in this report do not provide insights into the recent boom in youth e-cigarette usage (CDC, 2024).

Chronic Medical Conditions

As discussed earlier, over one-third of individuals postponed at least one type of care during the pandemic (Gonzalez et al., 2021). An important discovery in the literature is that receiving the COVID-19 vaccination has mitigated delayed or missed medical care by addressing concerns about virus exposure (Aslim et al., 2022). What are the implications of these findings for chronic medical conditions?

Firstly, the increased likelihood of delayed care may lead to fewer chronic conditions being diagnosed. Consequently, we might anticipate a decrease in the percentage of individuals reporting that they have been diagnosed with a chronic medical condition in 2020. Notably, this potential decline does not imply that people have fewer chronic conditions; rather, it is a consequence of delayed care and medical issues going unreported.

Secondly, due to the vaccine rollout in 2021, we’d expect individuals to feel safer and more inclined to visit a doctor for preventative care measures. As a result, we anticipate an increase in chronic conditions reported in 2021. However, since the mass adoption of the vaccine, we are also interested in the evolution of these chronic conditions over time. Therefore, we aim to study these hypotheses using the data on chronic conditions in KOMA and Detroit post-2021. Our analysis tracks trends in chronic conditions, including high cholesterol, coronary heart disease, stroke, lifetime asthma, cancer, depressive disorder, and diabetes.

From our analysis in Figures 22 through 31, two significant observations emerge. On average, the percentage of individuals with chronic conditions is higher in Detroit compared to KOMA. Specifically, the residents of Detroit exhibit larger shares of high cholesterol, heart attack, coronary heart disease, stroke, lifetime asthma, and diabetes. Meanwhile, mental health issues like depressive disorder are significantly higher in KOMA compared to Detroit. Figure 29 suggests that the racial depression gap between white and non-white KOMA residents has increased between 2022 and 2023. In both locations, white respondents disproportionately report higher rates of depression. Turning to gender, Figure 30 indicates that the increase in depression that has been observed after the start of the pandemic is primarily driven by KOMA women.

The reported depressive disorder proportions in Figure 29 should not be viewed as inconsistent with Figure 11; both highlight a deterioration in KOMA mental health. Figure 11 suggests that the racial gap between non-white and white KOMA residents has increased in terms of poor mental health days, with more poor mental health days reported by non-white residents. Meanwhile, Figure 29 finds an increase in the proportion of depression diagnoses among white-to-non-white KOMA residents, with white residents reporting more diagnoses. Consistent with Panchal, Hill, Artiga, & Hamel (2024), non-white citizens are less likely to receive formal mental health help despite reporting higher rates of poor mental health days within the last month. However, both sets of findings suggest that West Michigan faces significant mental health challenges, with over 25 percent of the population reporting cases of depressive disorder in 2023. Mental health problems can have adverse consequences on various facets of life, including academic performance, productivity, crime rates, and even suicide rates. Therefore, addressing these concerns through policy efforts and appropriate interventions becomes increasingly important.

The second major observation confirms our hypothesis regarding delayed care during the pandemic and the subsequent rollout of vaccines in KOMA. When analyzing the trends in coronary heart disease, stroke, lifetime asthma, cancer, and depression, we identify declines in 2020, consistent with the choice to delay care due to virus exposure. However, in line with the vaccine rollout, and feeling safer about reentering the doctor’s office, we report more cases of high cholesterol, coronary heart disease, stroke, lifetime asthma, cancer, and depression in 2021.

Furthermore, although there was a decrease in the percentage of individuals reporting coronary heart disease in 2020, there was a surge in the percentage of individuals reporting a heart attack in the same year. The increase in heart attacks may be tied to the individuals diagnosed with COVID-19 during the onset of the pandemic (Topol, 2020). These observations shed light on the complex interplay between healthcare access, delayed care, and the impact that public health crises have on chronic health conditions.

Figure 22: Ever Told High Cholesterol by Region, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 22 displays the prevalence of those reporting high cholesterol by region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that high cholesterol has decreased by 22.6% and 8.8% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. Similar findings are found in both regions.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

Figure 23: Heart Attach (18+) by Region, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 23 displays the prevalence of those reporting having had a heart attack by region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that heart attacks have decreased in KOMA by 28.6% and 23.1% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. Meanwhile, heart attacks have remained relatively constant in Detroit.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

Figure 24: Angina or Coronary Heart Disease (18+) by Region, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 24 displays the prevalence of those reporting heart disease by region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that heart disease in KOMA has increased by 0.6% and 0.1% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. Meanwhile, heart disease has remained relatively constant in Detroit.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

Figure 25: Stroke (18+) by Region, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 25 displays the prevalence of those reporting having had a stroke by region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that stroke has increased in KOMA by 38.9% and 8.7% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. Meanwhile, stoke has remained relatively constant in Detroit.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

Figure 26: Lifetime Asthma by Region, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 26 displays the prevalence of those reporting lifetime asthma by region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that asthma has increased in KOMA by 11.6% and 25.4% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. Meanwhile, asthma has remained relatively constant in Detroit.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

Figure 27: Every Told Cancer (Skin and/or Other) by Region, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 27 displays the prevalence of those reporting having had cancer by region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that cancer has decreased and increased in KOMA by 4.3% and 10.9% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. Meanwhile, cancer has increased in Detroit.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

Figure 28: Depressive Disorder by Region, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 28 displays the prevalence of those reporting depression by region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that depression has increased in KOMA by 7.4% and 23.2% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. Similar trends are found in Detroit.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

Figure 29: Depressive Disorder by Race, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 29 displays the prevalence of those reporting depression by race and region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that depression has increased in KOMA by 7.4% and 23.2% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. However, while depression is increasing among whites, non-whites show lower rates of depression.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

Figure 30: Depressive Disorder by Gender, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 30 displays the prevalence of those reporting depression by gender and region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that depression has increased in KOMA by 7.4% and 23.2% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. However, while depression is increasing among females, males show lower rates of depression.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

Figure 31: Every Told Diabetes by Region, 2011-2023

Description: Figure 31 displays the prevalence of those reporting diabetes by region. West Michigan KOMA includes Kent, Ottawa, Muskegon, and Allegan counties. East Michigan Detroit includes Oakland, Macomb, and Wayne counties. It shows that diabetes has decreased in KOMA by 5.8% and 13.3% since 2011 and 2020, respectively. However, a slight upward trend in Diabetes appears in Detroit.

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2023

References

Aslim, E. G., Fu, W., Liu, C. L., & Tekin, E. (2022). Vaccination Policy, Delayed Care, and Health Expenditures (No. w30139). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Berman, M., Crane, R., Seiber, E., & Munur, M. (2014). Estimating the cost of a smoking employee. Tobacco Control, 23(5), 428-433.

Cawley, J., & Meyerhoefer, C. (2012). The medical care costs of obesity: An instrumental variables approach. Journal of Health Economics, 31(1): 219-230.

Centers for Disease Control (CDC). (2022). Tobacco Product Use Among Adults – United States, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/media/pdfs/2024/09/cdc-osh-ncis-data-report-508.pdf.

Centers for Disease Control (CDC). (2024). E-cigarettes and Youth: What Parents Need to Know. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/pdfs/OSH-E-Cigarettes-and-Youth-What-Parents-Need-to-Know-508.pdf.

Finkelstein, E. A., Trogdon, J. G, J., Cohen, W., & Dietz. W. (2009). Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: Payer- and service-specific estimates. Health Affairs, Web Exclusive. Retrieved from: https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w822.

Gonzalez, D., Karpman, M., Kenney, G. M., & Zuckerman, S. (2021). Delayed and forgone health care for nonelderly adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute.

Khorrami, P., & Sommers, B. D. (2021). Changes in U.S. Medicaid enrollment during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open, 4(5), e219463-e219463.

Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS). (2024). Healthy Michigan Plan County Enrollment. Retrieved October 7, 2024, from: https://www.michigan.gov/-/media/Project/Websites/mdhhs/Assistance-Programs/Medicaid-BPHASA/HMP-Docs/HMP_County_Breakdown_Data.pdf?rev=13251999eb18459ea4a3a0ed0199f914.

Panchal, N., Hill, L., Artiga, S., & Hamel, L. (2024). Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Mental Health Care: Findings from the KFF Survey of Racism, Discrimination and Health. Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/racial-and-ethnic-disparities-in-mental-health-care-findings-from-the-kff-survey-of-racism-discrimination-and-health/.

Song, H., Bergman, A., Chen, A. T., Ellis, D., David, G., Friedman, A. B., et al. (2021). Disruptions in preventive care: mammograms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Services Research, 56(1), 95-101.

Topol, E. J. (2020). COVID-19 can affect the heart. Science, 370(6515), 408-409.